all the birds and all the pebbles

Meghan Price | Through Line | United Contemporary

**images courtesy of: artist, Meghan Price; gallery, United Contemporary**

Meghan Price

Through Line

United Contemporary

May 23 - July 13, 2024

The other day, while we laid in the park, a friend of mine described a curse that was placed on her as a child by a Bulgarian witch, which tormented much of her early life. She speaks often of curses, deities, mystics, and systems of belief that, as I grow older, I find myself less prone to roll my eyes at or disassemble with logic.

I asked her how I might go about being more spiritual.

“The best thing you can do is to maintain a dialogue with the world around you,” she said. “Talk to your houseplants, and the fuzz between your toes, and the street lamps on your evening walk. Curse them, thank them, whatever—but keep the lines open.”

People assume, from afar, that I am already spiritual—maybe because I am sensitive, or prone to daydreaming, or because I write fiction. But those who know me, or my writing, know that I am rarely willing to lift even a toe from firm, knowable ground. My friend’s answer accounted for this reluctance. She did not ask me to take a leap of faith or to accept a specific tenet, simply to engage more earnestly with the material things that I already accept to exist.

So, I started talking to things. I talked to my bicycle, which I had never acknowledged beyond its utilitarian purpose, thanking it after each journey, giving the frame a little pat. I chastised my windows during their yearly cleaning, asking how they possibly got so mucky from 8 feet above the ground. I complimented the locks of red hair on the back of someone’s head a few steps in front of me. This was forced, to start, but became habit more naturally than meditating or exercising, which require me to carve out space from my day. Engaging the world immersed me further inside of it. I felt less distinct from my surroundings, less concerned about my place within them. And then I visited the gallery, parked myself in front of an artwork, and realized I do not need to remind myself to talk to it. The conversation has been happening for as long as I can remember.

Price, Meghan. Ravine. 2024, Handwoven cotton, stitched to canvas, framed, United Contemporary

Serendipitously, the show where this realization occurred is premised upon an artist’s spiritual and material dialogue with another artist, who passed away almost two centuries prior. Meghan Price’s solo exhibition, Through Line, expounds upon the work of a prodigious 19th century scientist and illustrator, Orra White Hitchcock. Hitchcock brought hers and her husband’s scientific research to life via paintings in ink and watercolour on fabric. She has an affinity towards pastel palettes (from which Price gladly borrows) and her balance of artistic fluorish and dedication to subject makes for pleasant viewing for scientists and laypeople alike.

On display at the exhibition.

While strolling the show, I mused over the initial moments of Price’s discovery of Hitchcock’s work, the mysterious pathways that brought this project to life. Even to the trained skeptic, these signals of inspiration have a spiritual quality which artists know better than to puncture with logic. We portray them as lightbulb moments or strokes of genius, but the direction taken is usually the result of a gentle probing along a path from which the fog never lifts. In other words—the result of remaining open to, and in dialogue with, the world.

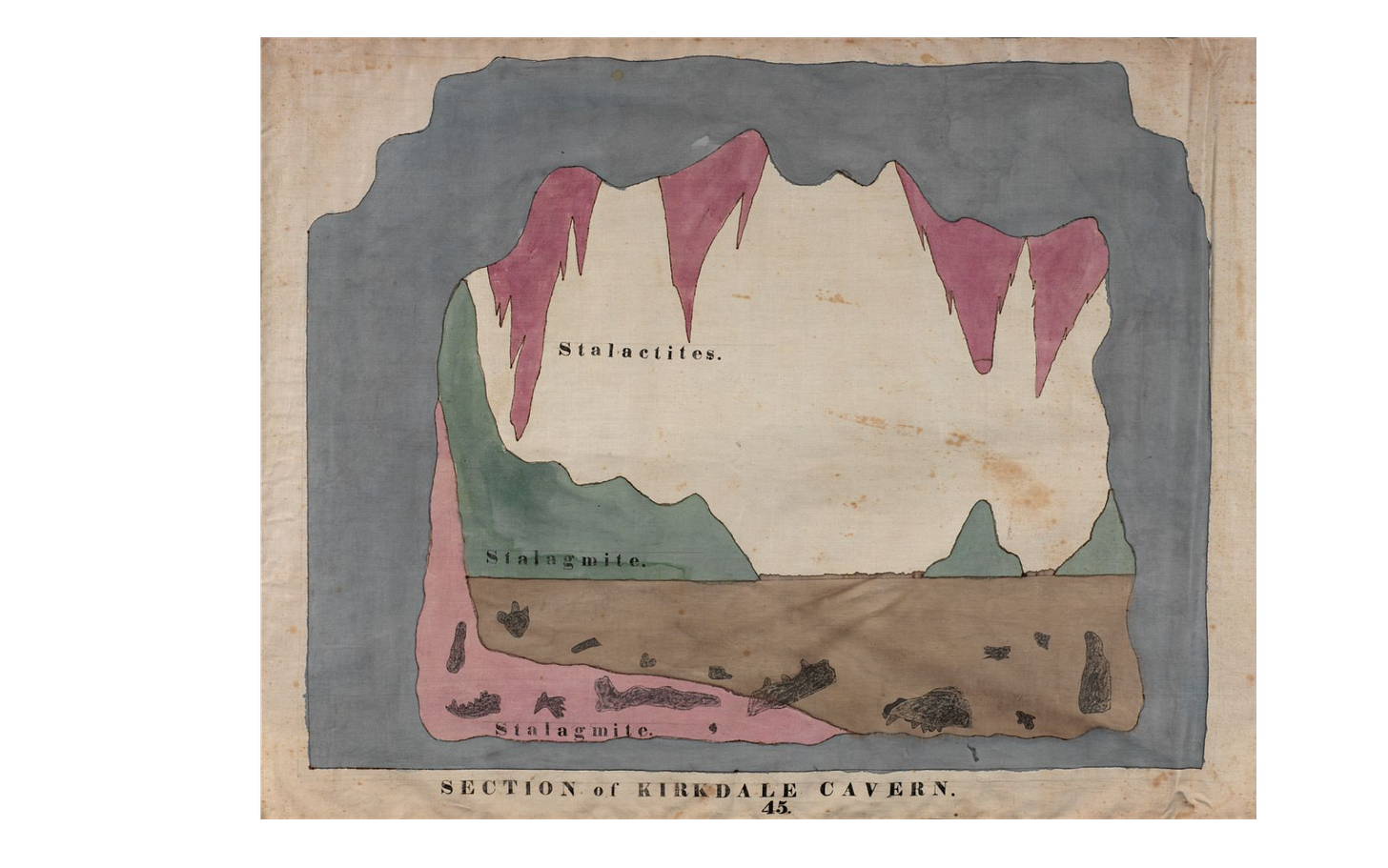

Hitchcock, Orra White. drawing of Kirkdale Cavern. 1828 - 1840, pen and ink on linen

Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library

I returned home from the galleries and took notes on works I had seen, hoping to arrive at some through-line for an essay. The exercise meandered in the opposite direction. I paraphrased my friend’s words on spirituality and sorted through my bookshelf, where I rediscovered a technical paper that I wrote 4 years’ prior, while working in metallurgical processing. Images of scarred earth from mining facilities I had surveyed, landscapes in Brazil and Colombia hubristically transformed, their scope reduced from trillions of living and non-living forms to a single element in my laptop battery. There I found that mysterious pathway, so easily missed; an access point back to Price’s work and, by extension, Hitchcock’s.

exhibition views, United Contemporary

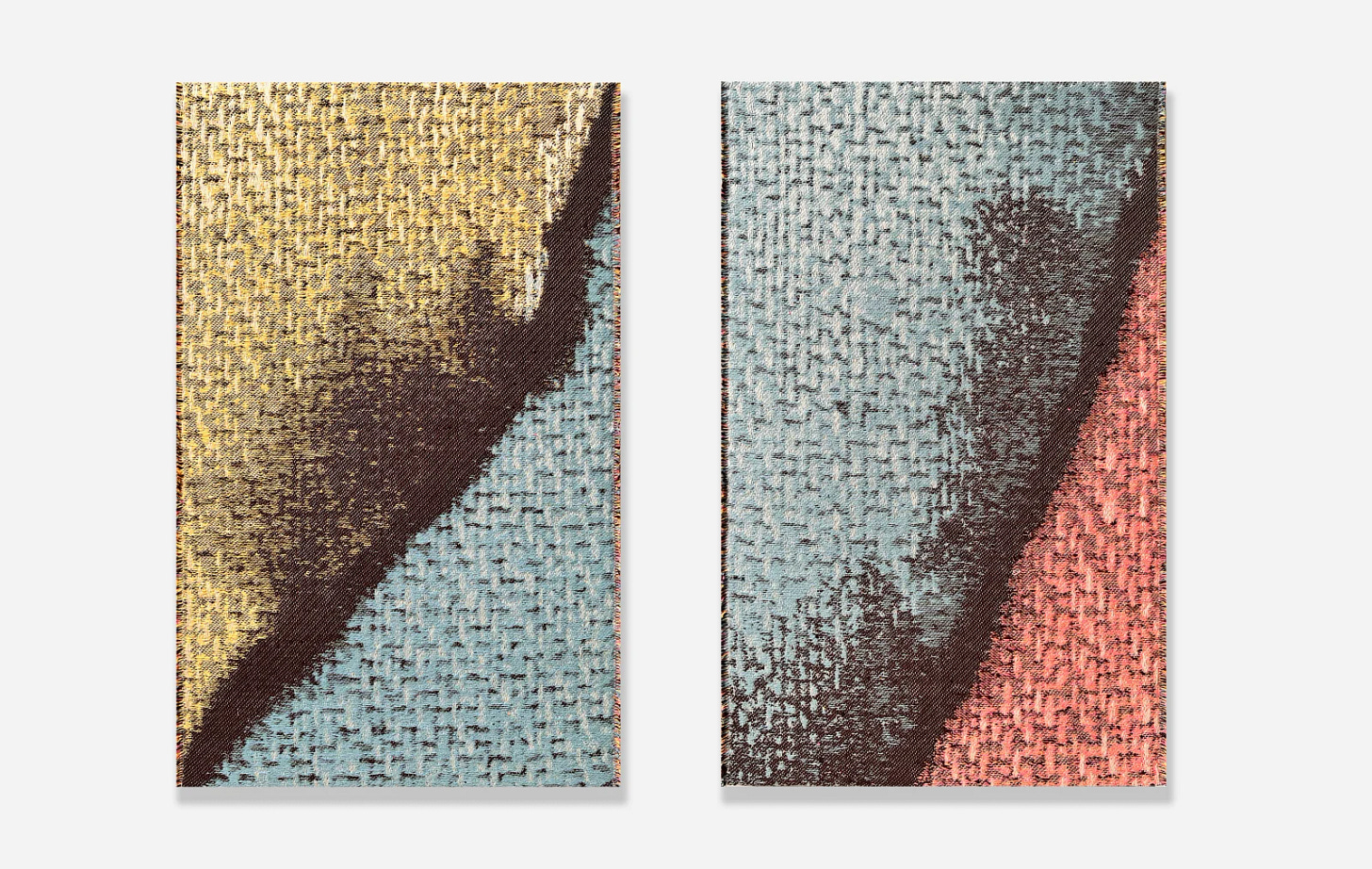

Hitchcock’s geological drawings portray earth from the top-down, while Price takes a bottom-up approach, extracting snippets of the illustrations around intersections, borders, strata lines, and blowing them up on canvas. Her sources are the results of empirical study, hard lines of scientific proof, but Price’s closer look captures something altogether less clear-cut, more transitive. It is comforting to treat the barriers between us and our surroundings as solid, complete. We ignore the jumble of the living and inanimate all intertwined. Sidewalks warp from forces above and below, weeds pushing through the cracks. Behind our drywall is a mess of itchy, pink insulation, mouse droppings, dirt, and insects. Construction worker’s coffee cups and cigarette packs decompose in the dirt beneath our buildings, eventually followed by cement and glass, the earth always reclaiming, combining, indifferent to our plans. Price’s work too, from afar, offers a semblance of structure and hierarchy. But the intricacy of the pieces pulled me closer, to blow them up as she did to Hitchcock’s work. I became lost in a mass of threads, hopelessly trying to follow a line from one edge of canvas to another. Isolation is impossible in an array of countless criss-crossing paths. Pulling one thread affects hundreds of others; take a few steps back and the landscape is ever-so-slightly altered.

close-ups taken by me, trying (failing) to capture the incredibly detailed thread work.

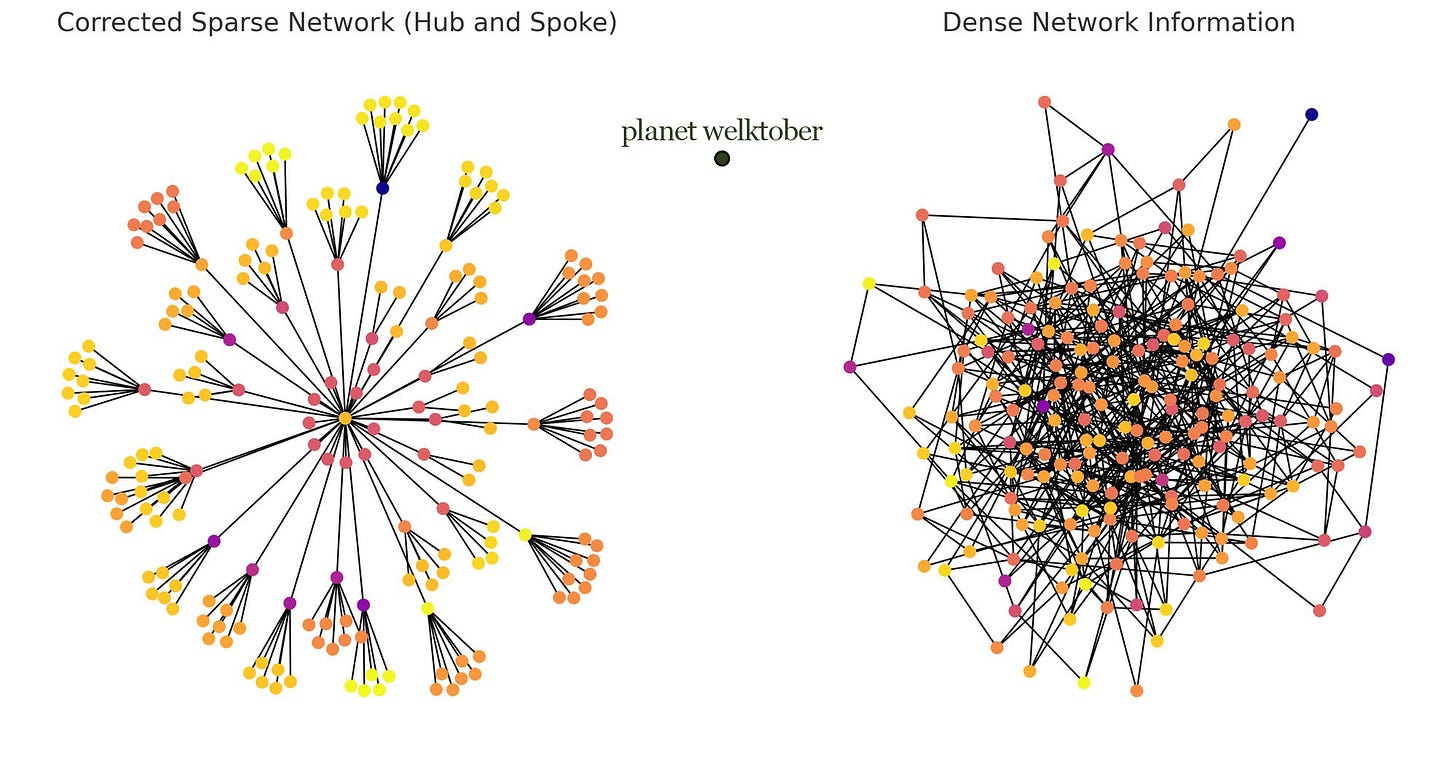

An article I was recently sent by another friend, Seeing Like a Network, illustrates the transmission of information across nodes (each of us is a node) which make up our information networks. These networks are ever denser and hyper-connected thanks, largely, to social media. The article was an overwhelming read. Each illustration of our interconnectedness (another example of technical concepts beautifully rendered) made me want to toss away my computer, to send out a mass text announcing that going forwards, I will only be accessible by mail. I wished for my node to be a distant Pluto.

original image courtesy of Strange Loop Canon

One less node in the network. One less smartphone, fewer ounces of nickel mined, emissions released, ecosystems ravaged. We are increasingly conscious of our knock-on effects in a material network, particularly one rooted in exploitation. We are overwhelmed by our information network, exponentially densifying, wondering where to take shelter. But in the shadow of a flightier, more spiritual network, I wonder if these other networks become infinitesimally small. Distant, indecipherable birdsong. Artists begetting scientists, scientists nurturing artists. Mist sprinkling our face and pebbles swallowing our feet. If exposed to everything, perhaps we gracefully return to nothing.

Price, Meghan. Vallies Bleed (diptych). 2024, Handwoven cotton, stitched to canvas, framed, United Contemporary

I flip through Hitchcock’s posthumous publications, showcased as part of Price’s exhibition, and run my fingers along drawings of an artist who knew enough to know that what she captured was fleeting, but captured it anyway. I edit this essay beneath streak-free windows, glowing smugly in the dusk as if in response to my earlier berating. From my bed, in the earliest hours of morning, the shadows of leaves sway in the wind like a projection upon my wall. I send forth molecules of ink from the aluminum tip of a ballpoint pen, sensitive to the tiny pressures and trajectories, pleased to be forming threads between art pieces in a room and the whims of my personal life, another line in the network, a speck of dust in your eye.

Those mystical things are so easily accessible.

To close, a poem:

The Wall, by Anne Sexton

Nature is full of teeth

that come in one by one, then

decay, fall out.

In nature nothing is stable,

all is change, bears, dogs, peas, the willow,

all disappear. Only to be reborn.

Rocks crumble, make new forms,

oceans move the continents,

mountains rise up and down like ghosts

yet all is natural, all is change.As I write this sentence

about one hundred and four generations

since Christ, nothing has changed

except knowledge, the test tubes.

Man still falls into the dirt

and is covered.

As I write this sentence one thousand are going

and one thousand are coming.

It is like the well that never dries up.

It is like the sea which is the kitchen of God.We are all earthworms,

digging our wrinkles.

We live beneath the ground

and if Christ should come in the form of a plow

and dig a furrow and push us up into the day

we earthworms would be blinded by the sudden light

and writhe in our distress.

As I write this sentence I too writhe.For all you who are going,

and there are many who are climbing their pain,

many who will be painted out with a black ink

suddenly and before it is time,

for these many I say,

awkwardly, clumsily,

take off your life like trousers,

your shoes, your underwear,

then take off your flesh,

unpick the lock of your bones.

In other words

take off the wall

that separates you from God.