As We Weep, So Too Does the Sky

Field Notes from Azadeh Elmizadeh’s current exhibition, Timekeepers

Azadeh Elmizadeh [link]

Timekeepers

Franz Kaka [link]

21 March - 19 April, 2025

all images courtesy of Franz Kaka, documentation via LFdocumentation

✎

Remember the art class activity where you cover an object with paper and rub a pencil overtop, imprinting the texture beneath? I vaguely recall this being one of my most exciting artistic breakthroughs as a child, only to realize that the maple leaves everyone else traced were just as beautiful as mine.

✎

This technique is called frottage. A term defined by the surrealists, not to be confused with dry humping (although I’m sure they wanted us to). It’s what Azadeh Elmizadeh used to develop the textured foundations of the 6 large paintings in this exhibition.

✎

During a visit to Iran, she would hike into the mountains surrounding the city of Tehran with bundles of linen, rubbing natural pigments into the material while pressing it against the rocky surfaces. She then rinsed the linen in streams and pools along the mountainside, further exposing the material to the elements and volatility of the landscape.

✎

I confess to knowing near-nothing of Iran beyond the smokescreen of Western media. My best reference for Tehran is from the minimalist cinematography in Taste of Cherry by Abbas Kiarostami. As Elmizadeh described her process to me, I relied on this stunted vocabulary, envisioning a lone figure in an arid, hilly landscape, with outlines of the city punching through a layer of smog and dust in the background.

✎

Uninformed as it was, this imagined scene of solitude, paired with the tactile interaction between artist, media, and landscape, felt deeply touching. The linens were steeped, quite literally, in history. Imprints collected were free from the distance and time which inevitably distort our perceptions of a place.

✎

An example of said distortion. My Indian heritage was instilled exclusively through family, at home, with few opportunities to make non-Indian friends at school. Not that I sought them. I was rebellious and resisted almost everything Indian about me. There was no hope in adopting a cultural identity that I couldn’t “find” myself. Today, regrettably, my conception of India is better defined by observations of first-gen immigrants to Canada and a handful of fading family traditions, than the country itself, which I have not visited since 2010.

✎

To rebuild those bonds to the country would require a process not unlike what Elmizadeh undertook in the early development of these paintings: a tangible, personal collection of experiences and interactions with the place. Perhaps with these lines established, I could develop or maintain layers of meaning from afar.

✎

And that’s precisely what the artist did. The imprinted surfaces traveled from Tehran to her studio in Toronto, where layers of meaning were developed with paint.

✎

I’m only a bit embarrassed to admit that when I first saw the faint, birdlike figures appearing in 5 of the 6 large pieces, my mind went to Pokémon the Movie 2000, where the legendary birds — Articuno, Zapdos, Moltres, Lugia — are revealed; another pivotal moment in my childhood (c’mon). I imagined catching a fleeting outline of the rare figures in the clouds, wondering if what I saw was real.

✎

The birdlike presence in most of the paintings, and its disappearance into the climactic, un-stretched piece at the front of the room (above) signals the ephemerality of the sighting. You stare into the void, hoping to see it again.

✎

The symbology of flight, disappearance and reappearance, paired with the knowledge of where these pieces began, further associates with ideas of migration and maintenance of tradition. The artist and the bird, perhaps one in the same, freed from the bonds of border, but coloured by their landscapes, symbols, histories of origin — even if, at times, the connections feel like a whisper.

✎

I am conscious of writing about an artist from Iran who presents work concerning it, and jumping to language like fleeing, loss, migration, etc. This has little to do with any one country; I bring my own baggage to the work. Such are the verbs which apply to my own relationship with my heritage.

✎

An excerpt from an essay in Anna Badkhen’s gut-wrenching Bright Unbearable Reality:

I think about the people around the globe who have gone through, are going through, such impotent dread, who also, day after day, worry about their loved ones far away; [...] each moment at least one person is missing for millions of us, often out of reach, flung apart as we are, undone transcontinentally. The grief makes it impossible to move: This is aporia, an absence of path, a passagelessness that engenders a state of powerless, immobilized confusion, of being at a loss, a no-way that is not the same as a presence, a separation of heart and will.

Yet there is something else: the connections that may fade but never disappear, the gossamer threads of intimacy we float behind us as we disperse, the kinship that may be undone in time but that our memories sustain as vivid, iridescent as a painted bunting's plumage. Picture the brief animation anthropologists sometimes use to demonstrate human impact on the planet—a pale, luminescent tapestry of roads, railways, pipe-lines, cables, air routes, and shipping lanes latticing a nighttime earth—except instead of physical infrastructure, imagine the other ways in which the Anthropocene connects us: the poly-threaded, shimmering veil of yearning and missing and care and love.

✎

The pieces, aside from one, are decidedly prominent in the small gallery. The warmth of them encroaches outwards. Typically when stepping into an exhibition, I do a quick scan of the layout from the entrance; in this case I was hypnotically drawn forwards to the centre of the room. There is symmetry to the pieces’ arrangement until, remembering to scan, I noticed a smaller painting off in its own corner near the entrance. I wondered about this outlier, titled As We Weep, So Too Does the Sky.

✎

For me, this piece functions as an entry point, or an exit, from the rest of the works which present as a series. It’s a cryptic dreamscape, depicting the sky’s response to a mourning ritual in which a gathering of women weep together, calling forth the respite of rainfall. Here, the sky weeps in return, its tears suggested to leave behind the extensive salt lakes in the country, and the salty waters in which the paintings were originally bathed.

✎

The large paintings in series contain elements of the sky, water, land, which the artist carries forth in spirit. This smaller piece captures the intertwining of the physical and spiritual in a cycle of tradition. The continuation of this tradition hinges on the ritual of reconnecting with the land.

✎

If the women are weeping for rainfall, what is the sky weeping for? Perhaps it is simply benevolent in answering their call. Perhaps it wishes to encourage them to keep reaching out. Perhaps it has witnessed, over the sweep of time, that those birds which once flew freely are less prominent; that when we abandon the work of seeking where we came from, tracing and carrying it forwards, the places cease to exist.

✎

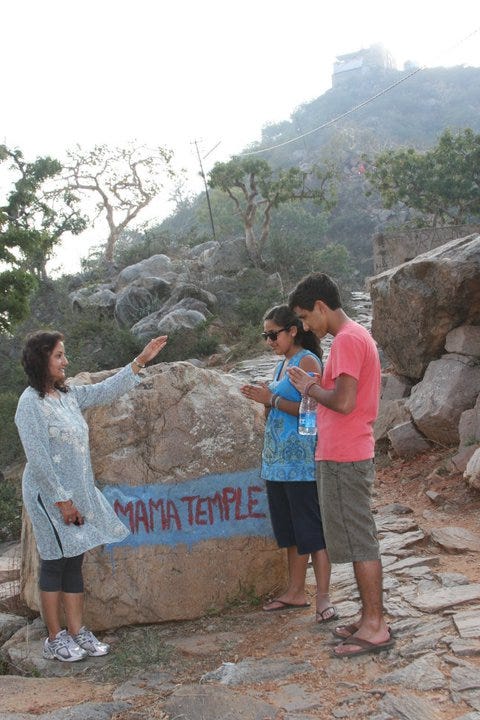

To close, some pictures from our last trip to Rajasthan, India, ~15 years ago.