From box-office Brutalist to a smol exhibition in Montréal

We’re talking about Carrara marble

~ I also write a bit about The Brutalist, but no spoilers! ~

I’m always fascinated to watch artists talking passionately about, or working intuitively with, their primary medium. It produces a sense of awe and envy not unlike that from witnessing a fluent exchange in a language I can’t speak. I felt the murmurs of this exchange during the climactic sequence in the marble quarries of Carrara, Italy from The Brutalist — my favourite amongst many great moments in the film.

The reverence with which the architect walks along the mountains of marble, shrouded in fog, is a lovely depiction of the relationship between artist and medium, in all its wonder and mystery — you need not speak the artist’s language to recognize it. His life was unraveling, yet he found peace amongst the materials of his craft. Perhaps they reminded him of the reason he pursued it in the first place. This relationship is contrasted by the clumsy presence of his greedy American patron, who seems immune to (or rejected by) the magic of the setting; he understands neither materials, nor art, as anything more than objects to exercise ownership over.

I feel like Carrara marble is one of those things people know about, but don’t really know about. For me, prior to writing this essay, it vaguely evoked Michelangelo’s David, and The Pantheon; I would surely fail to distinguish it from any other slab of expensive white stones. Instigated by the quarry sequence from The Brutalist, which is seared into my memory, I embarked on an unplanned trip of recollecting some instances where Carrara marble had featured in my life. I hope you find the result as satisfying as I did.

My first recollection, a day or two after seeing The Brutalist, was of a 2010 short documentary titled Il Capo. The documentary captures the labour-intensive extraction process of Carrara marble, guided by the artful hand signals of the titular Il Capo (the boss). His hand is missing the tips of two fingers, symbolizing the dangers of the trade. I wondered if the grizzled, anarchic quarry keeper in The Brutalist, who is missing a hand, was inspired by this character. It’s worth watching a few extracts of Il Capo here, if only to appreciate the chaos of the industry and the cultural (and literal) weight of the material. I saw the documentary long enough ago that I don’t remember where, or when, it happened — but I’m certain that it did.

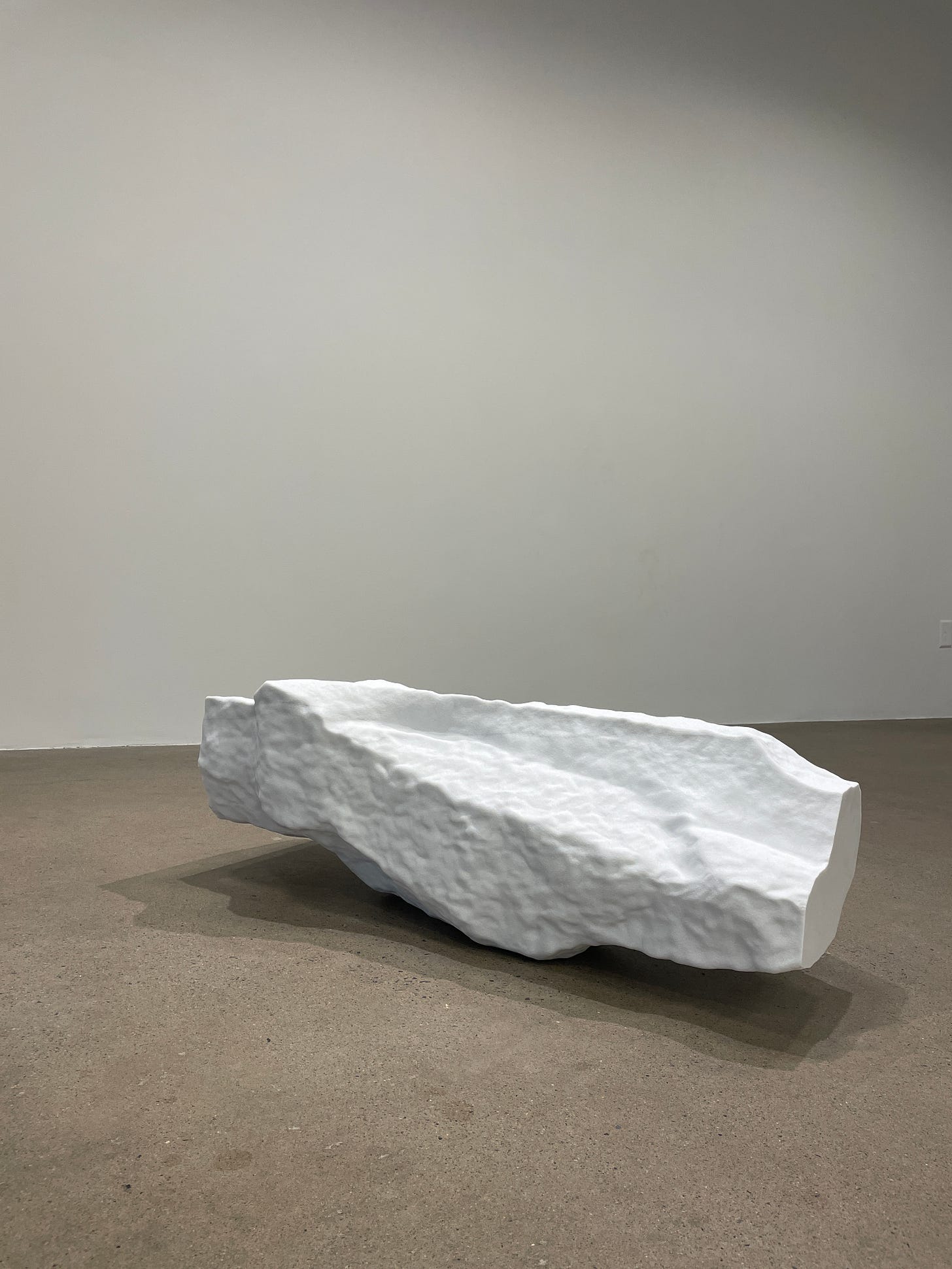

The next recollection occurred a few days after the above, with a far more recent memory. In Fall 2024 in Montréal, I happened across a monolith of marble in Marie-France Brière’s exhibition, Champ de contraintes, at Centre Clarke. It had been a long day of gallery visits. I didn’t read the exhibition text, did not think at all about the intention behind the artwork. I found myself stuck in front of the sculpture, overwhelmed by it, obsessed by the rippling textures, the immaculate whiteness, the realization that this was a naturally occurring chunk of earth. And then I snapped a few photos and carried on, thinking d*mn, that piece of marble was a banger. This is how 99%+ of my art viewing goes, don’t be fooled by the epiphanies in welktober.

After having seen The Brutalist, I was scrolling through photos and re-encountered the above image of the stunningly white marble. I now had the tools to wonder if it was sourced from Carrara, Italy. A bit of research confirmed my suspicion. The artist spent an extended period in Pietrasanta, learning to “read and write” in the language of the material. Not unlike the wizened quarry men who exploit weak points in the marble to detach it from the mountain, the artist infers, with hand and chisel, along the material’s folds, faults, and cleavages, formed by millennia of natural pressures, to arrive at her sculptures.

The final recollection occurred a few days after the above. I hopped on the streetcar towards the Financial District in Toronto for a dentist appointment. Arriving to the south side of First Canadian Place, I crossed through the palatial lobby to the north, where my dentist is located. I used to play squash in the gym in the basement of this building 4-5 days a week; accordingly, I picked a dentist and family doctor in the same location, and I have traversed this lobby hundreds of times. It was only on February 21st, 2025, however, that I paused to consider the obscene volumes of marble that not only lined every inch of the interior, but also the exterior façade of the building (the tallest in Canada at 298 m). I chuckled to myself, musing that the marble was probably also sourced from the Carrara quarries. A quick Wiki search confirmed that it indeed was.

I spent a while staring at the walls and enjoying the minimalistic fountain. It was lunch hour, and I recall noticing how many good-looking, well-dressed people there were milling about, feeling a pang of jealousy that I don’t work in an office anymore. I also noticed that almost every single person was on their phone, and guessed that each of them was surely as guilty as me for never once, in their daily routines, pausing to consider the material of this striking lobby and the stories it contains. That the lobby’s elegance relied on the obscure motions of a crippled hand from a disheveled quarry man. That some artists spend their entire careers listening to the whispers of this stone.

And then I carried on to my dentist appoint, for which I arrived 20 minutes late.

This is one of many themes from The Brutalist which speaks to art’s importance more broadly: where the raw materials of life are concerned, the entrepreneur turns them into something “productive”, while the artist, through the careful act of consideration, gives them meaning. This contrast is presented as conflict in The Brutalist, given the extremes of the artist and the businessman being somewhat caricaturized, paired with the unrelenting egos of the two characters. If ego (and anti-semitism, and greed, and a whole other whack-load of traumas) could be left behind, these two groups might’ve had much to learn from one another. They certainly do IRL.

Had I not seen The Brutalist, it’s unlikely that I ever would have taken a moment to reconsider Carrara marble’s historic significance, the quarry men of Il Capo, Marie-France Brière’s artwork, or the stones which make First Canadian Place a landmark. This is why I love art.

In other news:

I got a grant! It’s just a wee one for my short story collection (not welktober), but still means so much. Thanks to Ontario Arts Council and The New Quarterly, my first ever publisher, for support <3