mid-american fever dream

sipping concoctions with your shadow in a deserted Midwest town.

preamble

Today’s piece is inspired by a collection of works titled Midamerican Fever Dream by Summer Wagner. This collection (linked here) presents the artist’s cinematic, heavily-stylized photography as a sort of visual poem, punctuated by ethereal snips of audio, text, and animation for narrative guidance. I am wowed by how naturally this ambitious project is fulfilled through online presentation. There is a sense of wholeness and a clarity to the artist’s vision which curated, IRL exhibitions rarely achieve.

Themes of Rust Belt America and the mystical quality of our interior lives are at the core of this project, which I fatefully found amidst an avalanche of election + Halloween content. The work gave me a useful lens to process them. I thank Summer Wagner for showing up at the right moment and, of course, my relentless searching for new art (see: a good relationship to art is like fly fishing).

All images courtesy of artist, Summer Wagner (instagram / website).

essay

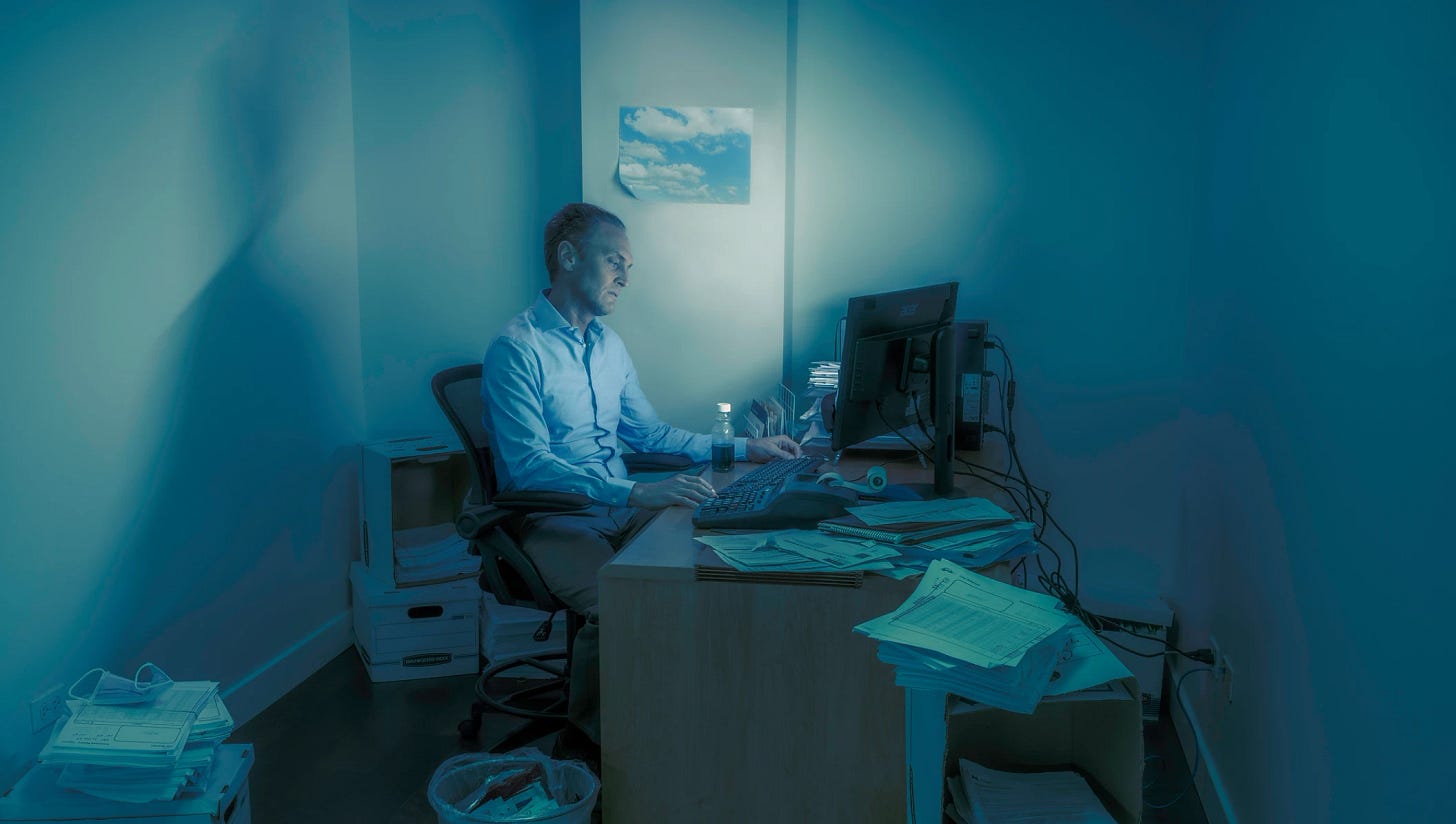

Those who spent a lot of time with me in 2017-2018 refer to the period as my dark era. During this time, my job, which I was clearly not suited for, had assigned me to a project which required me to fly in-and-out from a steel mill in Gary, IN, Monday to Friday, weekly, for 18 months. With each 48-hour stint back in Toronto, I compensated for lost time via a whirlwind of consumption and complaining and overspending which did nothing to alleviate my unhappiness.

Hence, dark era.

On the perpetually-delayed commuter flight to O’Hare each Monday, I would watch Toronto fade into the distance with the excessive sentimentality of a 2-day hangover. The plane ride was an uncomfortable exercise in slipping into a secondary, ill-fitting skin. After my first few weeks, I dramatically concluded that no amount of money, career kudos, or Aeroplan points would justify the sense of self-betrayal in greeting my colleagues at the rental car pickup with a forced smile and a pretence of excitement for the week ahead.

Everyone finds ways to ritualize their work, but for industrial operations, ritual is a necessity beyond mere convenience; it is a set of laws which minimize hazards and the enormous costs of downtime. In Gary, we clocked in-and-out at the same time, wore the same uniforms, had lunch at the same cafeteria with the same guys, caught a pint after work at the one pub by the plant. Being accustomed to downtown Toronto and the trust of a “knowledge worker” environment, stuffing in earplugs for a day at the plant felt akin to reducing an orchestra to a monotonous drone, a buffer from the highs and lows of real living.

It was thus an uncomfortable surprise when, after some months, I found myself cherishing the ritual.

To be clear, I am not attempting to stake any claim to the life of a steelworker. I was a corporate consultant LARPing as blue-collar; each weekend in Toronto I threw this ritual to the wind with $6 lattes and warehouse raves.

My fondness for the reliability of my weekdays nonetheless blossomed: being on first-name basis with the quintessentially maternal servers at the Great Lakes Café; peeling off my steel-toed boots at 3:30pm, followed by a long walk through a forested path from which you could almost forget the drone of the I-65. When the project (and the ensuing weekend of celebrations) ended, the vast openness of the months ahead in Toronto was purely daunting. For several weeks, I found myself lamenting the loss of ritual, an embarrassing realization after a year+ of complaining to colleagues and friends. Most shameful, perhaps, given the context of the infinitely more devastating loss of ritual that occurred in towns across the Rust Belt, like Gary, when plants downsized or shuttered, abandoning generations of tradition.

In Summer Wagner’s narrative collection Midamerican Fever Dream, linked at the top of the essay, the artist’s subjects of focus are individuals in Rust Belt towns who experienced the vanishing of an entire mode of living. The characters in the artist’s construction undergo an occultic ritual which serves to reckon them with their loss; in the artist’s language, they “undergo a process of encountering their shadow.”

I read the artist’s use of “shadow” as a notion of deep self, which I find effective on multiple levels. A photograph or video might seem a more comprehensive representation of self, but images, per Marshall McLuhan or as the image-maker intuitively knows, are defined by the manipulations and confines of the medium. Extending this logic, we are unlikely to find truth in a mirror; what we see reflected back is deeply distorted by ego. A shadow, conversely, is formed without interference. Sun and surface have no subjective input. Perhaps it is the purest representation of self we can claim.

Shadows, like ourselves, are hopelessly intertwined with the land upon which they are cast (and vice versa). And like the self, all it takes is a lapse in attention to forget it is there.

The characters in Wagner’s narrative have lost something fundamental to their identity. The small trough which resulted from the end of my 18-month ritual, described earlier, was quickly filled by another; I merely look back on that time through a lens tinged with nostalgia, a recognition that it immeasurably altered my shadow. A more substantial loss demands a reckoning which occurs not through the day-to-day motions of life, which serve largely as distraction, but through processes which confront our interior: therapy, art, grief. In Wagner’s case: a generationally-passed-down ritual inducing a fever dream. Through a process that can be interpreted as supernatural or otherwise, the characters seek means to be made whole again.

During my early days in Gary, I failed to see past the steelworker’s caricatures which they perpetrated intentionally or which I defined through my own filter (both, probably). Trump had recently been sworn-in, to the cohort’s vocal approval. MAGA hats and stickers abound. I observed, with smug anthropological distance, comments which bordered on (rarely intentional) bigotry, toxic aggression exposing fragile egos, and the suspicion which with they observed me — metropolitan, corporate, clean fingernails, hailing from their socialist neighbour to the north, telling them how to do their job.

In those early days, I was happy to affirm the outlines of my caricature. During night shifts I read Dostoevsky under a fluorescent glow of analytics dashboards in the dark control room while the operator watched MMA reruns. In heated moments, of which there were many, I maintained the infuriatingly detached, analytical language that a consultant is fluent in. My most revolutionary moment was renting a shiny Volvo XC90 for the week, presenting myself as the sole driver of a non-American-made vehicle on the plant.

In reinforcing these caricatures, both for ourselves and each other, we were collectively guilty of dismissing our interiority, our shadows; perhaps rejecting the existence of them. The steelworkers never could have guessed that I found more peace during my weeks in Gary that I did at home, and the internal questioning this caused.

Naturally, the caricatures fractured with time: I became more at ease with the steelworkers than my colleagues, for I never had to weigh my words around them; I watched the overworked area manager break down in tears on a call with corporate in Pittsburgh as they bullied the union workers over an equipment failure; one such worker playfully called me a homo upon seeing my after-work outfit, then divulged that both of his sons “turned out super gay” with hilarious resignation; the terrifying mud-gun operator whom, after seeing me almost shit my pants due to a vapour explosion from molten pig iron contacting a puddle of water, brought me a bag of cherry tomatoes picked from his garden for my Friday flight home.

In the early 70s, the U.S. Steel Gary Works employed over 30,000 people. This number dropped to 5,000 by 2015. The decline in employment was accompanied by an episode of (mostly) white flight. By 2013, the Gary Department of Redevelopment had estimated that one-third of all homes in the city were unoccupied or abandoned. An emergence of significant gang activity awarded the town the slogan, deserved or otherwise, of “the murder capital of America”.

Aside from the plant and the designated site cafeteria, my company barred us from exiting our vehicles in Gary. Our hotel was in the neighbouring town of Merrillville. The visual transition as we drove from abandoned Gary to the textbook-suburban Merrillville, where white people existed in droves, exemplified the fickle reality of American Dream. Gary was once a poster child for it.

Summer Wagner introduces a new construct of American Dream, one which occurs in our deep interior and remains unavailable to us, and others, unless we seek and unleash it. The work is a reaffirmation of self, a reminder to explore and remain in touch with your interior and to be wary of leasing it off to invented entities outside of your control: towns, corporations, markets, political parties. Yes, these constructs hold value, forming our livelihoods, values, relationships, and more; yes, the “self” is an invented entity, too. But as we rise from bed each day and stand in the light, it is only from ourselves that we can be sure to cast a shadow.