no intelligence req'd

celebrating art that AI is too "intelligent" to make.

images courtesy of,

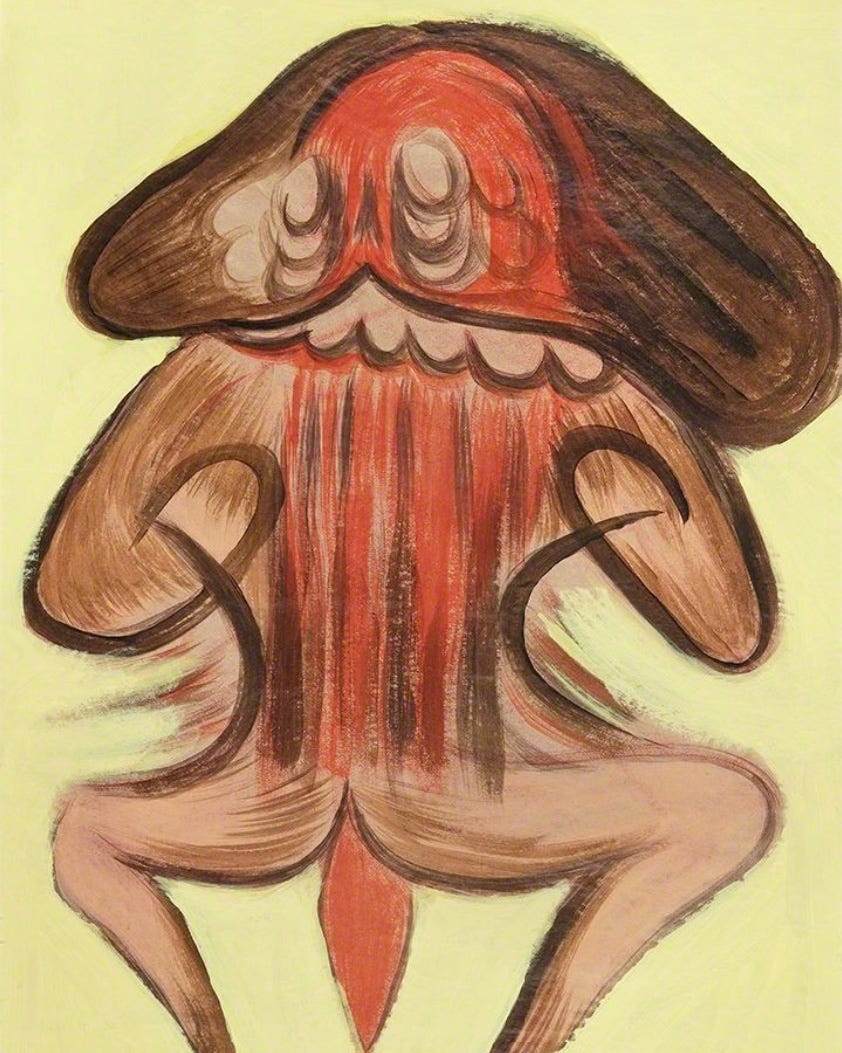

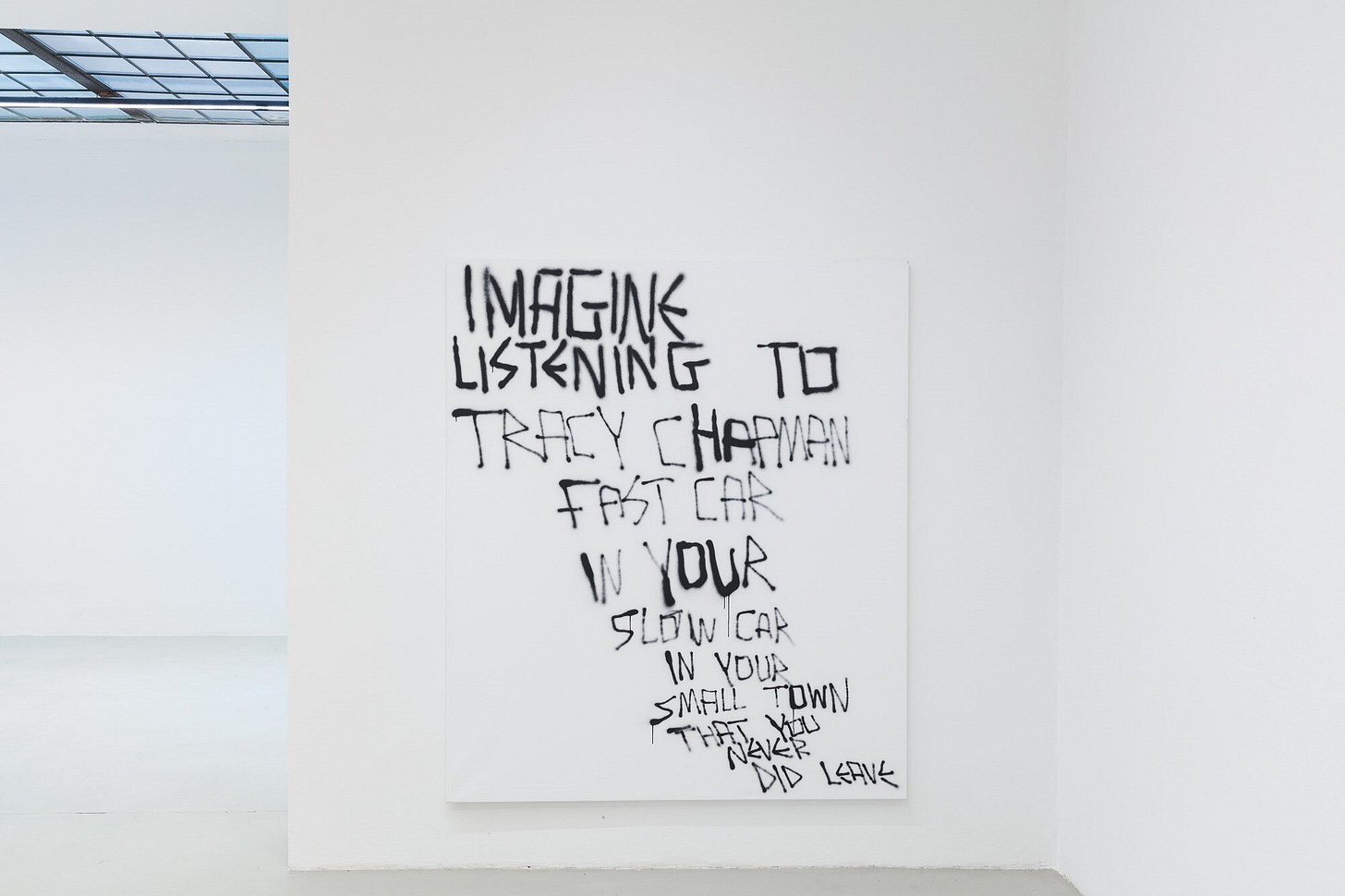

artists featured: Richie Culver, Nickola Pottinger, Nicholas Zirk, Chitra Ganesh, Daniel Guzmán

galleries: COOPER COLE, kurimanzutto

It doesn’t take much scrolling through social media comments, or listening to bewildered exhibition reflections, to know that the general public is skeptical (at best) towards contemporary art.

This skepticism can usually be boiled down to a few arguments:

contemporary art is out of ideas and compensates by ascribing meaning to things that are not art.

contemporary art is intentionally esoteric so it can feel superior to those who don’t “get it”.

contemporary art is a money laundering vessel for the rich.

There is some truth to points 2 and 3. The inaccessibility of contemporary art is undeniable (and the reason welktober exists). And while the commodification and tax rules around art reflect more on our society than the industry, it’s a problem nonetheless. I would argue, however, that these issues have little impact on the art being produced (point 1). They are surface stains on an otherwise thriving and essential process.

Today I make the case that this skepticism or apathy towards contemporary art is not just lazy, but also DANGEROUS, because in a moment where artists feel unprecedentedly threatened by AI, it reinforces a false notion that our artists are replaceable.

Read on!

contemporary art is not a monolith

It is a placeholder term for art created in the present. This window of time is arbitrary, but we might call it the past ~30 years. The term also has an avant garde connotation, meaning that it is concerned with new or experimental ideas.

Every era has had a contemporary art movement. Only with hindsight can we brand a period of time or set of artists with a concrete genre or movement.

disliking contemporary art is lazy & predictable

Pick any moment on the pendulum of art history and you will find a large and vocal cohort of haters of its contemporary art, who yearn for some arbitrary lost golden age.

But per the previous point, the art movement they are placing on a pedestal was once contemporary art. And people used to whine about it in exactly the same way (yawn).

Examples in modern history:

The first group exhibition of impressionists in 1870s Paris (including Monet, Renoir, Degas, Cézanne) was greeted with derision and ridicule. The term impressionism was coined by critics as an insult. Nowadays, the contemporary art world is largely bored by impressionism.

Taken to an extreme, in the 1920s, the term “degenerate art” was adopted by the Nazi Party and applied to genres that would nowadays fall under the broad umbrella of modern art. “Degenerate” artists included Picasso, Kandinsky, Klee, Mondrian, Chagall + hundreds more. (More on the interesting story of degenerate art).

check yourself

Given the above, do you really want to be screaming into the void about how “my seven-year-old could do that!”, followed by a diatribe about the good ol’ days when artists had discipline, honed their craft for decades, etc. etc.?

It’s natural to lament the loss of art forms we’ve come to love. Change is uncomfortable, and when the pendulum swings, it tends to swing hard.

we had Joni ←→ now we have Charli

we had Nighthawks ←→ now we have instagram captions splatted on a canvas

But as “degenerate” as it might seem at times, we should remember that a core function—or obligation—of art is to reinvent itself so that it can keep up with, or ahead of, the cultural moment. This habit of self-reflection and reinvention, and all the stumbling in between, is the most human aspect of art-making. As AI tools improve exponentially, it might become the only aspect which remains within our domain.

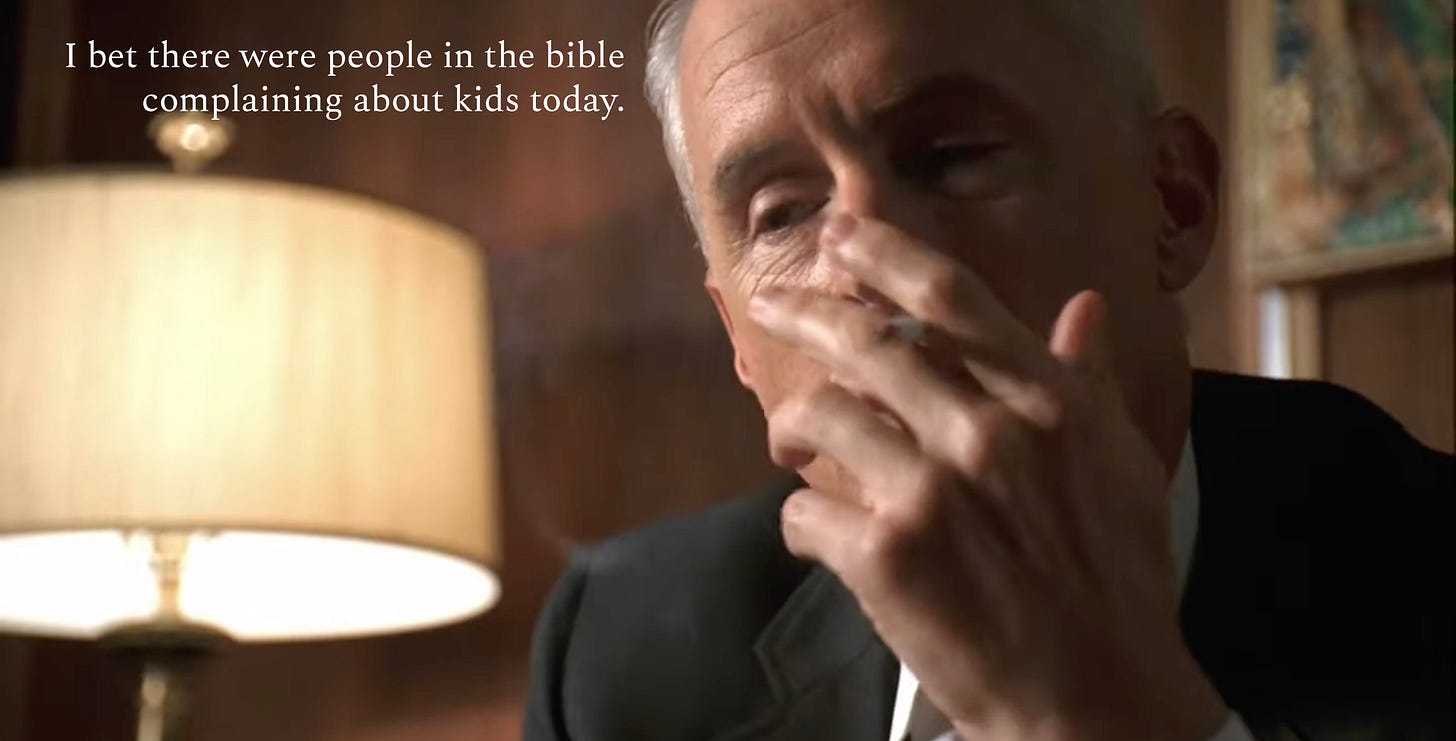

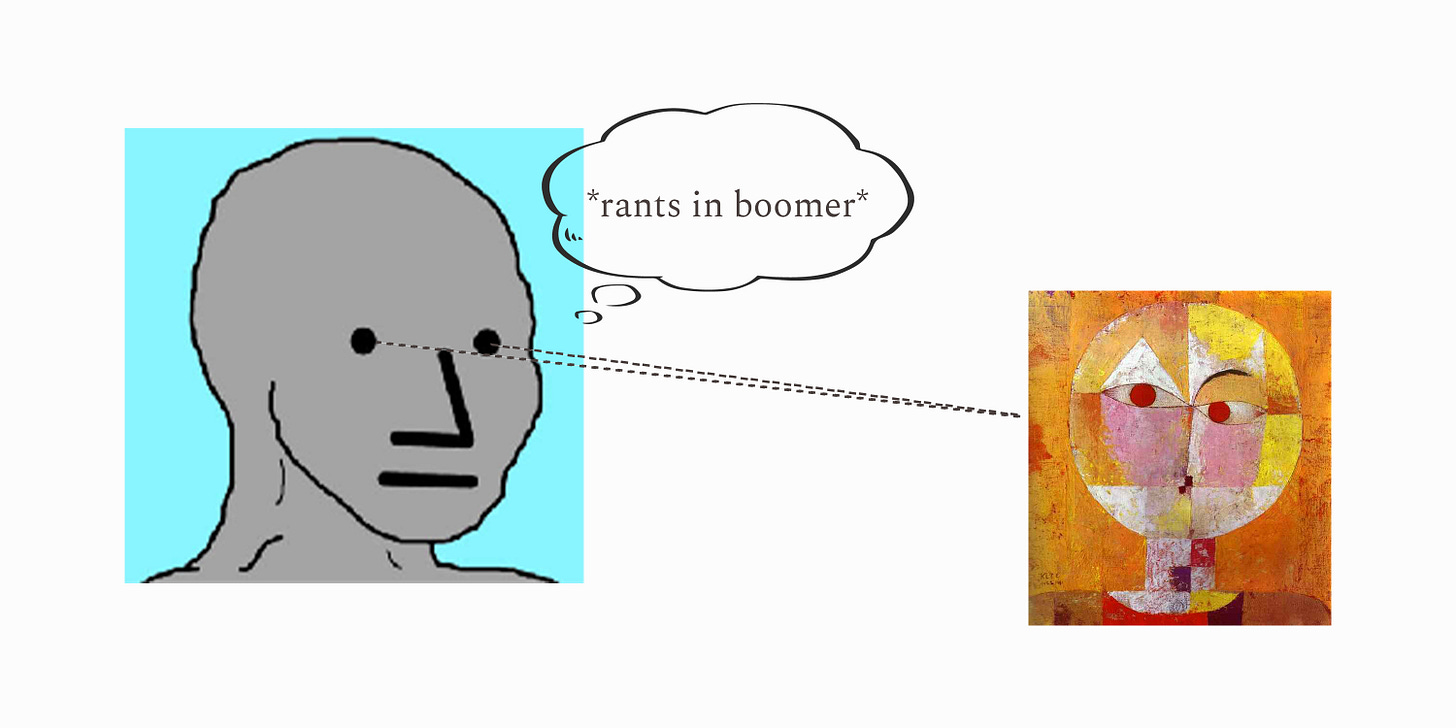

The text-based works featured earlier, by polarizing artist Richie Culver, hold a concise and comedic mirror to many facets of contemporary culture. The human element of this work is a quality that should be recognized and celebrated, rather than focusing on artistry as the ability to accurately capture a picture, or as a showcase of technical skill—both of which AI easily dismantles.

(Not to mention that Culver is capturing something accurately, albeit abstractedly, in his work, and this does take skill and talent).

AI tools are the most effective consolidators of history, ever. They easily out-compete artists who do little more than riff on styles of the past. Conversely, artists deemed “contemporary” are inherently producing something new by responding to the present. As consolidating voices become the norm, and everyone becomes an 8/10 artist (or designer, writer, etc.) perhaps the 9s and 10s are those who offer the unpredictability + relatability of distinctly human work.

Call me a stupid optimist, but I believe AI will make evidence of the human hand more cherished than ever—not unlike the clunky yet comforting embrace of in-person shopping following the pandemic explosion of Shopify templates guiding us frictionlessly to the checkout page.

Humans (perhaps to our detriment) do not seem capable of shrinking in response to expanding technology. The rise to prominence of the photograph threatened the work of realist painters. This prompted the birth of impressionism and expressionism, inviting human subjectivity into the art, rather than forcing artists to capture “reality”. Such was the catalyst for the arrival of pure abstraction some decades later. Despite being a demographic which feels amongst the most threatened by AI, and most vocally resistant to it, I believe artists are amongst the best-equipped to demonstrate their irreplaceability. If only we can avoid judging and confining them to irrelevant art historical standards.

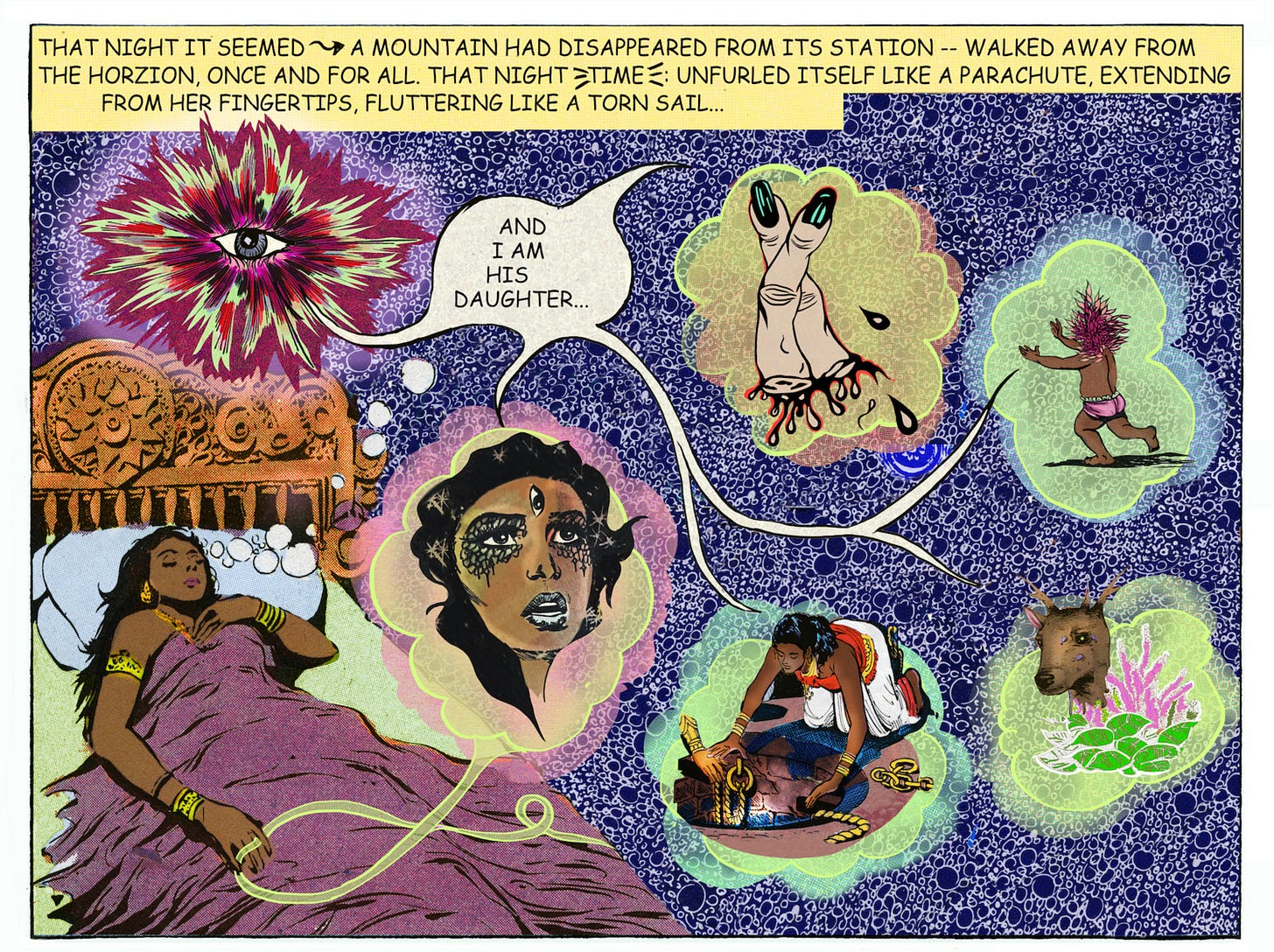

To me, each of the pieces included in this essay feel distinctly human. This captured humanity is a skill which many artists spend their entire careers searching for, their raison d’etre. Simultaneously, I have heard EACH of these artists’ work—online, or while eavesdropping at the exhibition space—accused of being “low skill”, “lazy”, or “garbage art”.

This form of criticism assesses the art in a vacuum, as a picture to compare to pictures from past generations, lacking context of the artist and what was happening around them. But Ernst Gombrich reminds us that “there is no such thing as art, only artists.” If we are not careful with our lazy assessment and dismissal of contemporary art, we are effectively handing the torch of the artist over to AI.

There is a better alternative: cheer on our artists as they degenerate and humanize art to new extremes, and enjoy the spectacle of technology sputtering to keep up.