Crying on the Treadmill

A story inspired by a lady at the gym.

To onlookers in the room, the exuberant wiggles that escape from Diane’s hips as she mounts the treadmill are registered, quite naturally, as a moment of frailty. She surveys the gym, her conquered kingdom, from the raised platform. After six months’ recovery, she has successfully resurrected her weightlifting routine without a whisper of pain or re-injury. Now she can relax. Throw on an episode of Normal People for her thirty-minute stroll at 3 mph and 1.5% incline. Gaze wistfully out the window at the winter landscape as if she were a heartbroken Marianne Sheridan exploring the boundaries of young adulthood on her year abroad in Sweden, rather than a late-middle-aged woman at a community centre in Toronto hovering her heart rate around 100 bpm because her doctor said so. She wiggles her hips once more; they feel sturdy, responsive, ready for action.

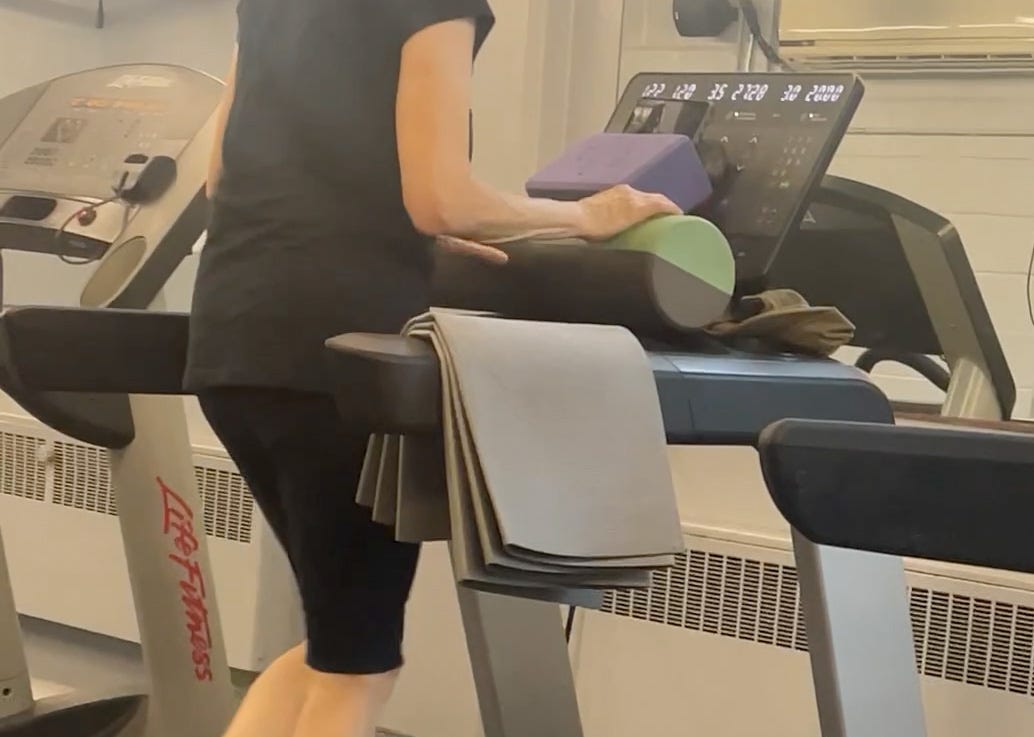

Her exercise mat, foam roller, yoga block, and five-pound dumbbell are bundled in her arms. Due to the gym’s filthiness, and its membership by men who mostly seem homeless, she prefers to bring her own equipment. Ever since one of these men (presumably) stole her AirPods, she also prefers to keep the belongings within arms reach. She hangs the mat over the treadmill’s right handrail, places the foam roller in front of her, its edges supported by the left and right handrails and its midsection braced against the front console, stacks the yoga block atop the the roller, the dumbbell atop the block, and finally balances her phone—rotated horizontally for widescreen viewing—atop the dumbbell. This delicate, tower-like structure, supported along the slope of the treadmill’s console, positions her phone at a height that minimizes the craning of her neck. She punches in the treadmill settings, presses play on episode ten of Normal People, and starts walking.

Despite being a paying Amazon member, her stream is interspersed with several minutes of ad breaks. The first ad, for Dubai Travel, suggests that Dubai is a better destination than Paris, Rome, and London (ha!). She hates this ad. Despite having the media literacy of a “boomer”, according to her niece and nephew, she easily recognizes it as the “AI slop” they keep complaining about. While trying to mute the ad with the tiny button on the screen, she takes both hands off the foam roller, which starts rolling down the handrail towards her chest. Her phone lands in the water bottle holder as she scrambles to secure the block and the dumbbell. She reassembles the structure, excusing her clumsiness as an opportunity to practice her fine motor skills while walking. Multitasking is good for the brain.

In the first minutes of the episode, Connell learns that his friend from high school, Rob, has committed suicide. The poor boy can hardly handle his emotions on a good day. Diane wishes to step inside of his grief, but her phone keeps sliding out from its tilted position such that the screen faces the ceiling. After a few instances of returning the phone to the correct angle, she tries swapping the positions of the yoga block and the dumbbell, thinking the grippy-ness of the foam block might better hold the phone in place. Unfortunately, the block is larger than the dumbbell, and when she takes a heavy step on the wobbly treadmill, the block’s unsupported front edge tumbles forward, sending the phone to the treadmill track, and subsequently, to the floor behind it.

She pauses the treadmill and reclaims the phone, forgetting that her hands were bracing the foam roller, which rolls the length of the handrail and lands at her feet. The yoga block and the dumbbell have fallen to the treadmill track. She feels the pressure of surrounding gazes as she collects the items and rebuilds the structure, this time hanging the exercise mat over the console rather than the handrail; the cushiness of the material might provide more friction for the objects than the slick plastic. She also shortens the structure by relocating the dumbbell to the water bottle holder, sturdying the column at the cost of a few degrees of neck strain. This seems to work; the foam roller only requires the pressure of one finger to stay upright. Her breakthrough is diminished, however, by the exercise mat preventing access to the buttons on the console. She digs her hand under the mat and presses a button that feels important. Thankfully, the treadmill returns to life.

Diane gasps when Marianne shows up, unannounced, to Rob’s funeral. Despite the tragic circumstances and the tedious presence of Connell’s new girlfriend, the tension between Connell and Marianne is palpable. Rob’s grieving father calls Connell a “good man”, causing Connell to break down; he does not feel like a good man. The surge of emotion Diane had been anticipating since the opening scene extends from some invisible depth of her soul, settling into a lump in her throat. Her nephew is exactly Connell’s age, in his first year of university; she cannot bear to imagine him facing such a loss. With her misty eyes she steps too far forward on the treadmill and catches the tip of the mat, whose bottom edge is dangling near the track. The mat is tugged downwards, sending the items on the console tumbling. She pauses the treadmill and blinks the tears from her eyes before reassembling the column, this time ensuring the mat is hung such that the bottom edge dangles closer to her knees.

The episode is around the halfway point. Marianne is back in Sweden and Connell is depressed. They’ve started Skyping each other. Marianne leaves the call running overnight, so the first thing Connell sees upon waking is her figure bathed in brilliant morning light as she works at her desk. Diane is deeply touched by this. She faintly recalls the nourishment of starting a day in the presence of the man she loved most in this world, and prays, sheepishly, that she might experience a fraction of that feeling once more. The Skype scenes are perhaps her favourite from the series thus far, but there is a man standing somewhere behind the treadmill speaking loudly in her direction, disturbing the moment. She pauses the stream, removes her headphones, and presses buttons at random through the exercise mat until the treadmill stops.

“Can I help you, sir?”

He is not looking at her; he is talking gibberish to himself in her general direction. His sweat-soaked t-shirt is glued to his skin, his nipples visible through the white fabric. He smells like urine. The edges of his Tim Hortons cup are frayed into oblivion; she imagines little strands of paper disintegrating into his mouth with each sip. She sighs and turns back around, presses START on the treadmill, and resumes the episode. Now the stream is playing an ad for BetRivers Casino. This one is even more brazenly “AI slop” than the previous. The actors’ faces lack a single blemish. They are perfectly smooth and symmetrical, as if sculpted from marble. Their expressions are entirely misaligned to the script.

The ad transitions abruptly to Connell’s full-blown meltdown with his therapist. Paul Mescal really is a terrific actor, she thinks, as she weeps in earnest. She walks with a wide gait to avoid her teardrops patterning the treadmill; stepping on them seems like a bad omen. Her sobs are drawing attention from the men in the room. Let them stare, she thinks. At least she’s being noticed—if only for a few minutes. She wonders if women of her age are even more irrelevant to the world than these homeless characters, who are, at least, a noteworthy thing to evade, to walk around with a large radius and avoid eye contact with. For better or worse, her invisibility has never been so openly acknowledged. Perhaps that’s why these men have gone outwardly mad; it’s the only way anyone will pay attention to them. She regrets these unkind thoughts but they have already come and gone.

She notices, through her peripheral vision, a young man on a stationary bicycle holding his phone at a suspicious angle—perhaps he is trying to film her? In twisting her neck to catch him in the act, a familiar pinch in her upper-spine sends a jolt through her spinal column. Her hands jump to her neck, releasing the foam roller and collapsing the items to the treadmill track. She massages her shoulders, wondering how many weeks this small incident will set her back, how many sleepless nights it might cause, then pauses the machine. She gathers her belongings from the floor and faces the young man, perhaps in his late-twenties, early-thirties, still staring at his phone, trying to be “nonchalant” the way her niece and nephew always are when they stare at theirs. She glares into the dead, unseeing eyes of his phone camera. Yes, that’s me, I’m the old, neurotic bitch balling her eyes out at the gym. Here for your entertainment.

She rebuilds the column, crying gently. Her repetitions have paid off; the structure’s balance is perfect. She does not even need to support it with her hands. While the third round of ads is playing, she has the bright idea to mute her headphones rather than the stream, preventing any risk of displacing the phone. She watches the snow fall out the window, relishing the corporation’s wasted advertising dollars. This is what her niece and nephew would call “touching grass.” Normal People resumes. The closing scene is idyllic; a lighthearted Skype exchange between Connell and Marianne, Connell looking hopeful for the first time in months, and the lovers’ tender, straightforward declaration, before the end credits, that they miss one another. She closes the app. The blurred screen of the treadmill timer—her eyes are, once again, damp—hits thirty minutes. She dismounts the machine, sanitizes her equipment and hands, then wipes the salty sweat and tears from her face. The stiffness in her neck has mostly settled. Between the crying and the completion of the workout, she feels as if a great weight has been lifted.

Such are the triumphs, she supposes, that keep us treading along.