Nostalgia Bomb

Call the sentimentality police!

After a week spent in my adolescent home in Calgary for the wedding of my oldest friend, it’s only natural that I open the flood gates on some art concerned with nostalgia. I owe most of my fiction to that famous mood. It’s an impulse I am constantly picking fights with—but more on that later. Let’s first introduce four Canadian artists, each with sculptural practices that explore the sentiments tied to everyday objects.

Kellen Hatanaka, whose exhibition, Stolen Heirlooms, is currently showing at the bows in Calgary, AB;

Stephanie Temma Hier, from Toronto, now Brooklyn-based;

Erica Eyres, whose exhibition, Memory Problems, opens next week at Norberg Hall in Calgary, AB;

Laura Moore, Toronto-based, whose dual exhibition, Ctrl + Alt + Delete, opens this Saturday at Tom Thomson Gallery in Owen Sound, ON.

This letter was first inspired by Hatanaka’s show, Stolen Heirlooms, which I visited while in Calgary. With paper, wire, and washi tape, the artist delicately recreates and reclaims possessions that were lost or abandoned during the Japanese-Canadian internment of WWII, honouring the legacy of his family’s experiences, and losses, from forced incarceration.

The stories attached to these objects were erased and supplanted with memories of fear and xenophobia. In recreating them, the artist returns the objects to the shelves they were meant to gather dust in, reinfusing them with sentiments they were robbed of. This act of nostalgia is not saccharine or juvenile, as nostalgia is so often cast; the indulgence of a fictive past allows for the reconciliation of generational loss.

But need we justify our own nostalgia with such a meaningful purpose? The remaining three artists, as far as I am aware, do not connect theirs to anything grandiose. There is always a loss, however small, to be wistful over. The past is inevitably fictionalized, and nostalgia makes for great stories. Walking by my junior high and the parks where I used to meet friends, I feel whispers of a presence long absent in my adult life—and maybe for the best. Impulsive, egotistical, dying to impress. A trail of wonderfully embarrassing stories. Yet I can’t help but lament the decisiveness with which he was abandoned.

Many of us, especially men, enter an emotional trough which extends between the indulgent years of adolescence and the “earned” sentimentality of later life. Feeling too much in the valley is rarely encouraged; this is the time for building life’s resume, not wistfully reading it over. Observations of the men in my parent’s generation suggest that emotional channels rekindle when there is more life in the rearview than ahead, more space and hours to reflect. Finally, we are so lenient to grant ourselves the decadence of sentiment without the charge of sentimentality.

I am wary of the fuzzy line between the two and the pejorative perception of the latter. Sentiment is the feeling; sentimentality is excessive feeling for the sake of itself, shallow and performed. The definitions might be valid, but I’m concerned about our habit, particularly men’s, of self-policing this divide. Sentimentality is the quality I most heavily police my own writing for. The closing paragraph may very well be guilty of the crime.

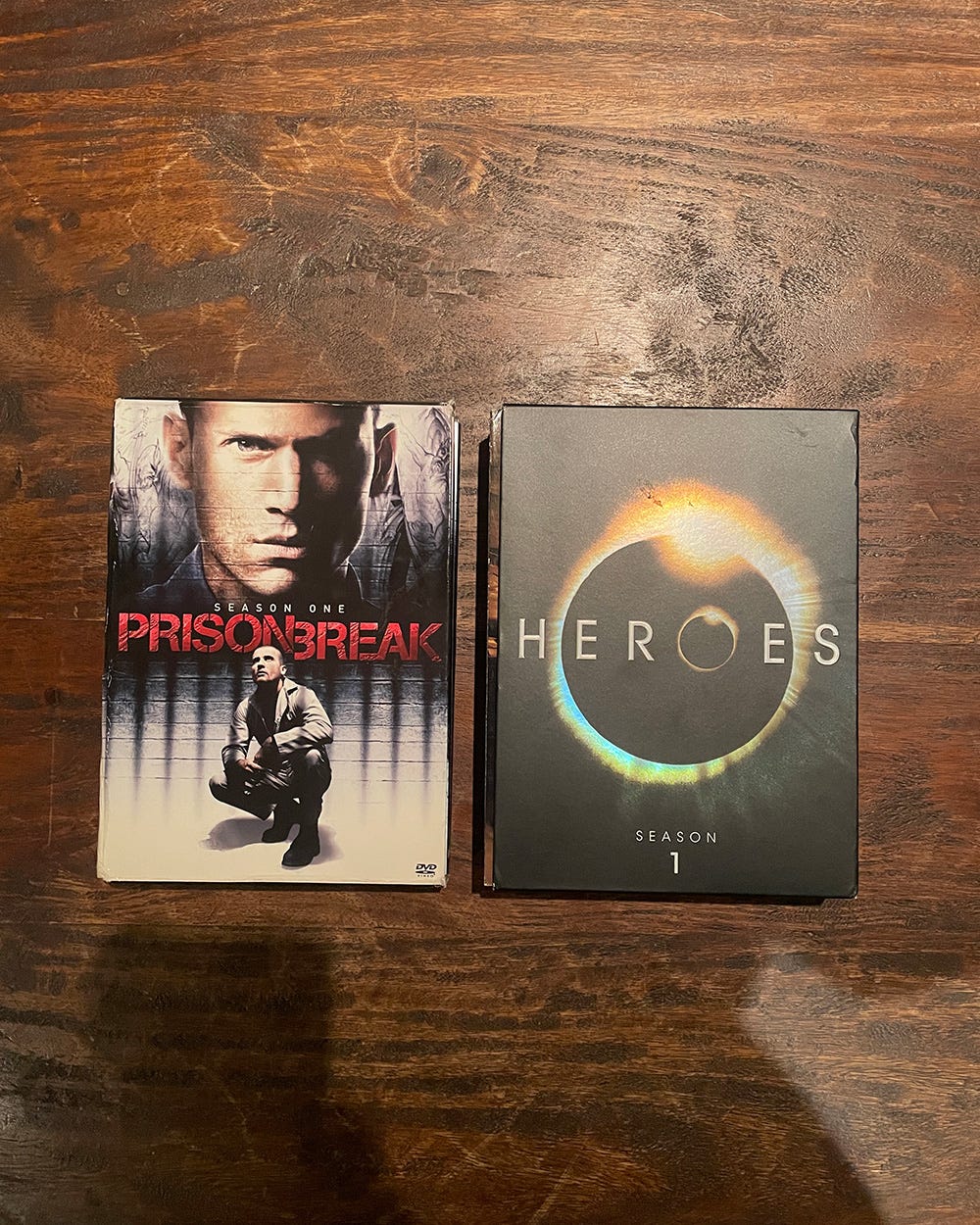

In life, as in art, it is safer to avoid sentiment. Vulnerable sentences are so easily replaced with a postmodern sneer. More than once I’ve heard one of the best songwriters of our generation, Adrienne Lenker, get accused of being overly sentimental. But for those in the depths of an emotional trough, who are locked outside of their feelings, sentimentality (loving the sentiment), that juvenile indulgence, could be the door key. The first step towards the feeling. The embrace of objects of nostalgia—an old DVD, the school courtyard, a deck of cards—might just flood the trough and lift you out.

I came here for the wedding of one of my oldest friends. We closed out the celebrations at 3AM in his mother’s house, making one final mess of the place, smoking her slims in the kitchen like she would when we gathered there as kids. A sense of closure on the ride home, with the solstice light teasing the day, my eyes revolting the hour, my face sore from smiling. Seven hours later, I woke to an empty home and breakfast supplies left out by my parents. I poured a mug of coffee and moved cautiously through the empty rooms, fidgeting with memory-infused objects I used to chastise my parents for hoarding.

Of course, I get it now.

The world just goes along. Nothing much matters, you know? I mean really matters. But then sometimes, just for a second, you get this grace, this belief that it does matter, a whole lot.

- Lucia Berlin, A Manual for Cleaning Women

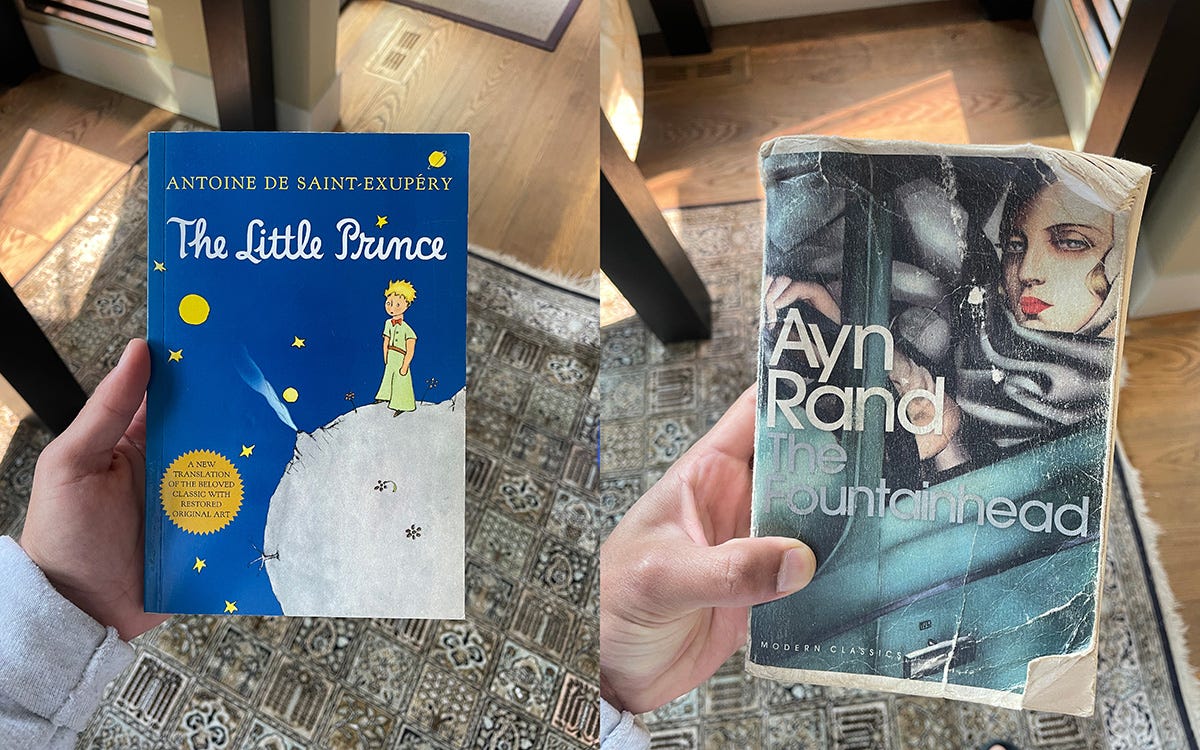

A few objects from my adolescent home: