Romance is the Only Option

Notes on art, romance, and isolation from Mexico City

Good morning everyone. I’m starting this letter from the patio of a small café in San Rafael, Mexico City. It is dusk. To my left, food stall owners sing songs as they sponge down their carts, sharing buckets of soapy water. To my right, in a small plaza, a group of dancers has gathered. They range from young adults to late middle-aged and practice a slow dance to a tinny, portable speaker playing Natalia Lafourcade. At a fire station across the street, bomberos are clearing the busy sidewalk to train an 100m sprint down the block. Three racers get in position, geared up in firefighting suits. After taking off, their colleagues gather around to cheer, arm-in-arm, as the racers charge across the finish line and buckle over in exhaustion.

This symphony of activity is a constant here; in three days I have already somewhat numbed myself to the visual overload.

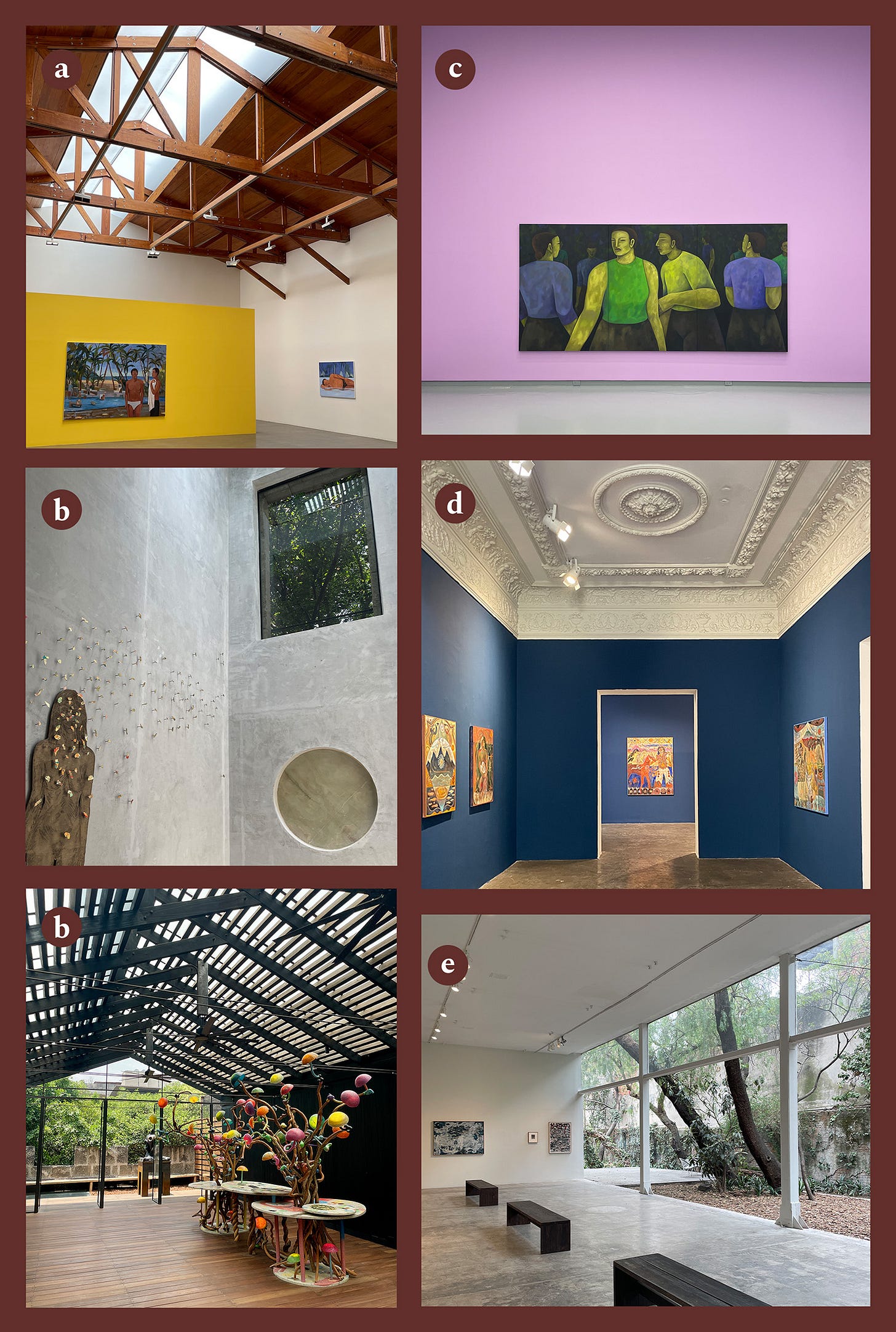

I came here to see art. On each day, I visited three galleries, covering the distances between on bicycle, trying and failing to avoid highways, collecting a film of dirt as trucks transporting god-knows-what lurched alongside. Thankfully, contemporary galleries in any city can be relied upon for pristine bathrooms to freshen up. Also thankfully, the galleries were excellent. Not just the art but the spaces themselves. They seem less constrained than Canadian galleries, often experimenting with colour, bold design elements, and integration with exteriors. It is particularly reassuring to see art in the presence of outdoor plants. They are having a conversation we are not privy to.

In 10 hours I’ll be taking the earliest flight out of the city, to Oaxaca. I meant to sit at this cafe and write a listicle-esque gallery guide, but predictably, having arrived here from a colourful Indian wedding, and with the approaching end of my stay, I am far too inundated by romance + nostalgia to trade in bullet points. Even the little cucaracha which just scuttled past my shoe and into the gutter is infused with some higher purpose. So please bear with some slightly looser, more meandering observations.

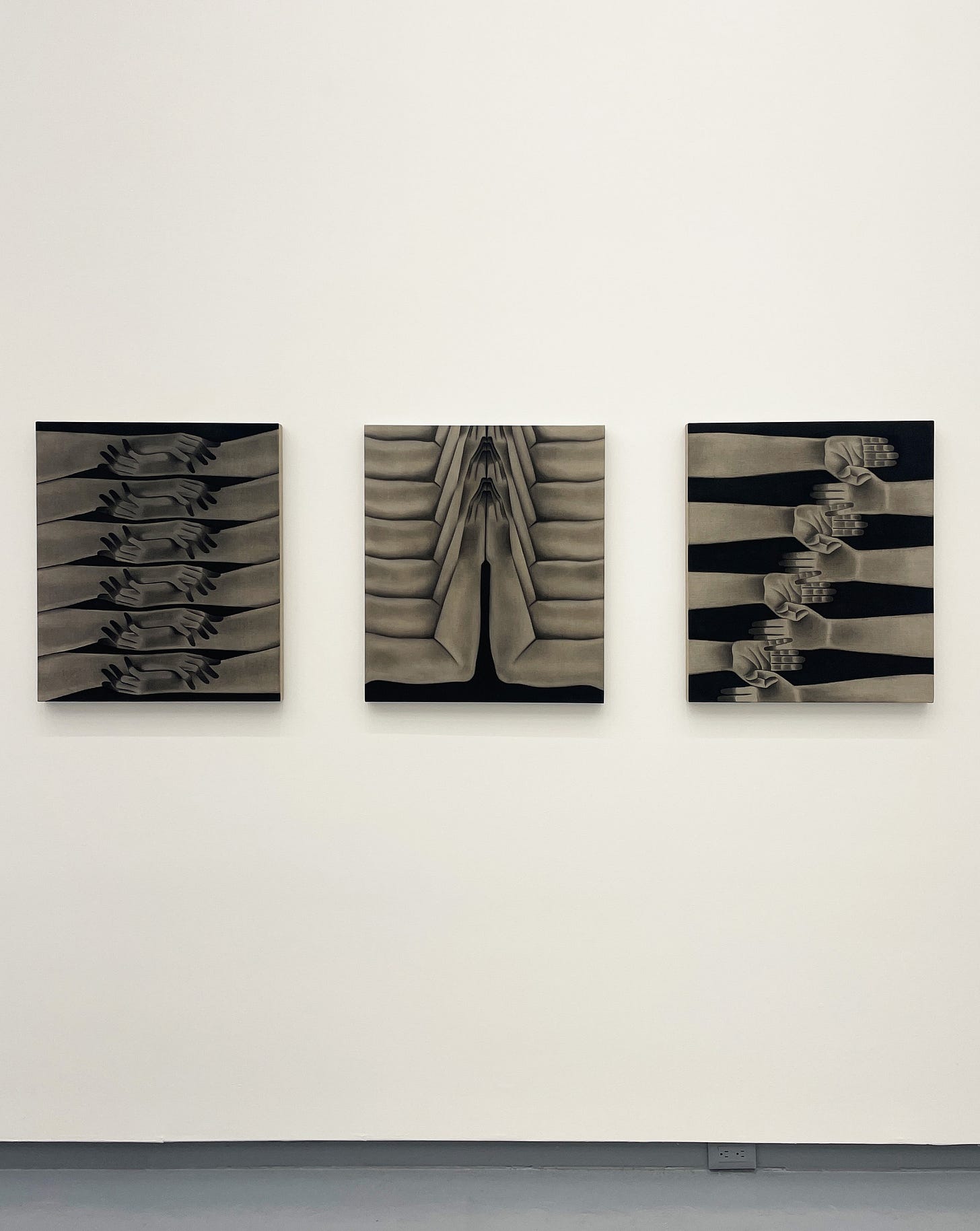

The best exhibition I saw this week was Hilda Palafox’s, also known as Poni, titled A una palma de distancia [A palm’s length away] at Proyectos Monclova. The artist’s enlarged figures move through an ambiguous, foggy environment, a setting which would feel hopelessly desolate were it not for their gestures of outreach, the focal points to each piece. There is a performative, choreographed quality to their movements, as if a degree of spectacle provides the momentum required to overcome an environment which so fiercely discourages reaching out.

The pieces centre around communication via touch. I interpret this as a sort of back to basics: as language breaks down and trust in images erodes, perhaps we return to a means of communication that can’t be short-circuited. To embrace touch, however, would be to embrace an instinct that we’ve largely repressed, and for obvious reasons: it’s been abused time and time again, pandemics, ppl with long, unkempt fingernails, and so on. The touching instinct has not only atrophied but morphed into its polar opposite: fleeing to occupy the emptiest spaces, protecting said spaces fervently. By default, we lend a wide berth on the sidewalk, find the most isolated spot on the subway, and apologize for spending a half-second too long in someone’s “personal space”. These milder instincts boil up to our walled fortresses which contain every possible gadget, never permitting a stranger’s fingerprints on the belongings we use a few times a year. In such an environment, the idea of reaching out and touching, particularly with someone we hardly know, becomes an act of impropriety. Some would say this outcome was necessary; I find it sad and boring.

Having written all of that, I am still sitting at this café in San Rafael, scanning examples of physical and emotional human connection from left to right. Amongst the first things I jotted down: If the artist believes there is a social problem in Mexico, a visit to Canada would quickly re-romanticize her to her country. I recall my first-ever salsa class in Toronto, some weeks before this trip. The teacher had to drag us off the walls to pair off like teenagers at a school dance. When the music and instruction stopped, partners would throw their hands away from each other as if touching a hot stove. To realize that people in cities like Mexico City are lamenting their social well-being, relative to which Canada’s is near-primitive, suggests that our crisis of isolation lives more prominently in our perception than our lived condition.

We are bombarded by imagery of social abandonment, bolstered by stats & diagnoses, memes satirizing our loneliness, all of which diffuse into the notion of a permanent condition. Disconnection becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The artist implicitly acknowledges this insidious perception through the empty spaces in her works. Gaps exist inside of the paintings — physical impediments between humans such as walls, or the spaces between outstretched limbs — and outside of them, in the use of diptychs and triptychs creating space between panels. Though often small, the gaps are felt. In keeping them ambiguous, the artist is not suggesting a specific condition of disconnect that plagues us; not smartphones, politics, whatever. The emptiness is not concentrated in Mexico City, or Toronto; pick any place and you’ll find the perception that our social selves have been abandoned. But importantly, the artist does not linger on these gaps. They are an emptiness from which the hopefulness of the work emerges. The artist gives agency to her subjects, who reach through the fog they have cast themselves within. The illusion is punctured by a moment of bravery.

Now I am at the beach with some friends in Oaxaca. We rented beach chairs closely sandwiched between two groups of Mexican travellers. The group on my right is three girls, roughly my age. Hoping to practice my Spanish, I follow their conversation and try to find the right moment to interject. There is eye contact and polite smiles, enough encouragement to proceed, but I don’t find the right moment. And neither do they. We allow the disconnect to settle. The two feet between our chairs seems to expand with each minute. Then, a laughably simple act dispels the myth: the middle-aged lady to our left asks if we’ve tried a Coco Loco. She hands over a coconut full of gin and coconut water. When it is finished, she has the coconut cut open and hands it over again, telling us to try the meat inside. In Mexico, we share everything, she says, in response to our polite refusal. She invites the three girls to our right into the conversation by telling them we are getting the gringos drunk. Soon enough, and with minimal effort, we are all sharing Coco Locos in the sand.

This is socializing 101, you might be thinking. Especially if you’re outgoing. But Palafox’s work is a reminder that sanctifying these small moments, giving them a performative, theatrical (and actionable!) quality, might be the best defence we have against our intensifying perceptions of isolation.

Some hours later, I am back in Mexico City for a layover during my route home from Oaxaca to Toronto. Almost 5 hours, overnight, still fuzzy from the Coco Locos. I contort myself awkwardly in the airport seating, trying to get horizontal. The weird sleep prompts weird dreams, including the Inception moment where you are falling right before you wake up. I grasp at the air in a rapid start. My outstretched lands upon the head of a young man who sits on the other side of the tandem row of chairs. He was sleeping too. Lo siento, lo siento, I say. He laughs at the graveness of my apology. He takes my hand, puts it back on my head, gives it a couple pats, and we go back to sleep.

Finishing this letter from the plane as we descend into Toronto, listening to the saddest music I could find, coaxing out the post-travel blues which are starting to press in gently. The sadness is not about returning to work or routines (I miss both) but a cliché feeling that home is inadequate. That the likelihood of encountering a scene similar to the opening of this letter is non-existent; that I will sit at a similar café only to see bodies rushing past, headphones on, miles of traffic each containing a robot in his private, air-conditioned pod, opting to engage with a podcast host rather than people. But then I will remember that this, too, is how Hilda Palafox likely sees her home of Mexico City. The onus rests with me, and us, to reject such perceptions, to reach out through eyes, mouth, and hands, to pretend every place we encounter is a wellspring of chance and romance, teeming with potential. And should this feel too difficult, should society feel too repressive, we can seek the same, at minimum, through art. Enough pretending eventually makes it true (manifesting, as the kids say).

I disembark the plane and head directly for a water fountain. I despise buying bottled water; having to do so in Mexico meant that I was mildly dehydrated for the last two weeks. My bottle is under the fountain and I press the button. Cold, clean water, and it's free. A moment of glee. He remains a gringo despite every effort.

Your words really stayed with me… 💗💐thank you.

They hit something deep, something about how romance might not be only for dreamers, but a necessity to all. A way of staying alive, staying open, staying human.

It reminded me of an old New Yorker piece that i once read and beyond reaching for each other, there’s also touch, and the quiet power it holds.

And maybe that’s what we’re all craving now, not just contact, but connection. Not just presence, but presence that lingers… right?

https://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/power-touch

Agree completely with supporting human touch and expression! Sounds like an amazing trip. Well done Rishi!