how much cyborg is too much

on degrowth, e/acc, and the allure (myth?) of a natural life

Father John Misty’s Things It Would Have Been Helpful to Know Before the Revolution is a portrait of life in a post-progress society following a revolution to avert earth from climate catastrophe. The depiction is not a greener pasture of frolicking, noble savages — it’s a bored population which well-remembers the conveniences of the past amidst their newfound earthly struggles. Towards the end of the song, “visionaries” start introducing products to make life more convenient. We know the rest of the story.

Now I mostly spend the long days walking through the city

Empty as a tomb

Sometimes I miss the top of the food chain

But what a perfect afternoonFather John Misty, Things It Would Have Been Helpful to Know Before the Revolution (2017)

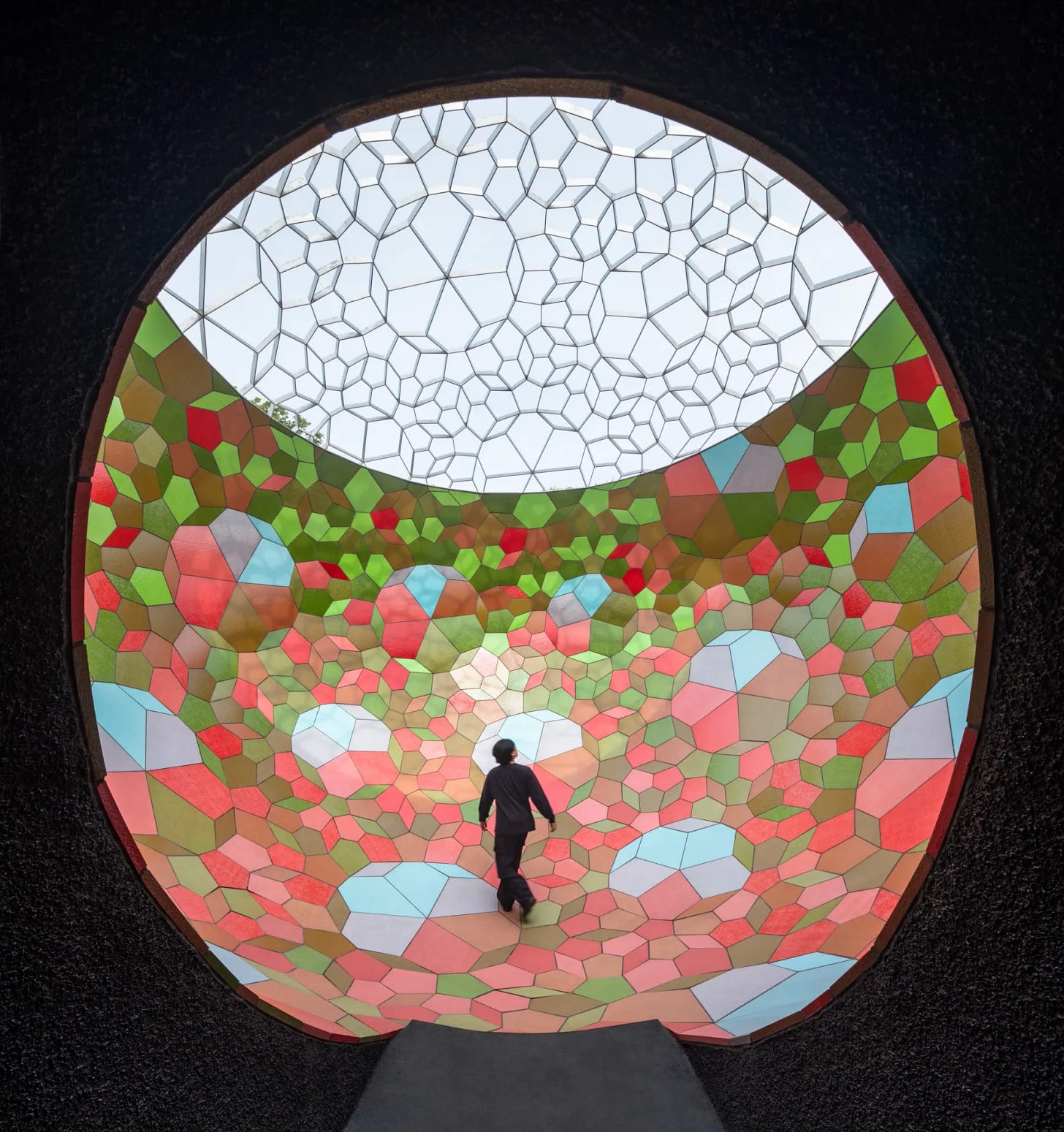

The song satirizes the lifestyle that might be required to meaningfully change our parasitic ways. It indirectly pokes fun at those whose idea of a more sustainable future is a patchwork of vague yet comfortable images, a Potemkin Village as flimsy and shallow as an AI-made video, or a dream. If only our cities looked like Rivendell or Caladan — more waterfalls and buildings nestled into green hills, fewer cars and cigarette butts — our minds could finally rest at ease.

The Great Debate

As we know, the discourse around our response to the environmental / climate situation culminates in two extremes:

a dramatic change to human behaviour.

often referred to as degrowth, though I don’t love the branding (critics call its proponents decels), since it’s more of a shift in growth focus from hard units like GPD towards human and ecological well-being.

massive technological shifts which permit us to continue on as we are (requiring, in the short term at minimum, further destruction of nature).

often referred to as effective accelerationism (e/acc for short), which argues that nature is a competition, there is no “equilibrium”, and that the best way to maximize benefit for humans is to continue our domination via accelerated growth and expansion.

metastasized, ironically, from effective altruism.

thought leaders in this camp had a big W with Trump.

see: BasedJeffBezos (decels: take notes on branding).

We cruelly dominate nature to thrive (#2); the next phase of thriving might require us to thrive less, or redefine what it means to thrive (#1). This dilemma makes it seem like the above options are a zero-sum game — extremists in either camp might agree — but a balance between them almost surely needs to be struck. Response #2 alone is a big, scary gamble which rests mostly in the hands of people I don’t trust. Response #1 alone — well, just refer back to Father John Misty’s song.

Even though most people can probably accept the idea of balance above, believers in change to human behaviour (like me!) tend to be cast as delusional, perhaps nowadays we are libtards.

Rational, realistic people seem to place all or most of their eggs in response #2.

I like response #1 simply because it’s the one I have a degree of control over as an individual. I’ve always hated feeling like the wide-eyed dreamer that gets patted on the head when I talk about dumb little behaviours that I think are helpful. I’m trying to come to terms with why this position feels so naïve. Maybe I’m right to be naïve.

So here I explore three typical arguments which deflate response #1.

1. Behavioural change comes from the top down.

This argument is the most prevalent one pitted against proponents of behavioural shift. Despite its shortsightedness, it seems to be widely touted as a fundamental truth.

I feel self-conscious for writing something this obvious, but for whoever needs to hear it: To abandon individual agency because the world is comprised of other individuals whom we can’t control is to neglect that these individuals, like us, have agency — that political parties and corporations are made up of said individuals. If one is unwilling, as an individual, to make sacrifices they believe in, they can’t blame businesses and politicians who exploit the environment in response to their needs.

This is a thinly veiled admission of not wanting or having the willpower to change one’s behaviour. It’s fine—most people don’t. Just say that instead.

2. We only want the sexy parts of a natural life.

This is a better argument which goes back to the core debate between #1 and #2.

Nature is discomfort. Few statistics suggest that our efforts to abandon it to current extremes make us proportionally happier, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to relinquish the comforts we’ve accrued. It requires a massive re-envisioning, not a shallow romanticization, of discomfort.

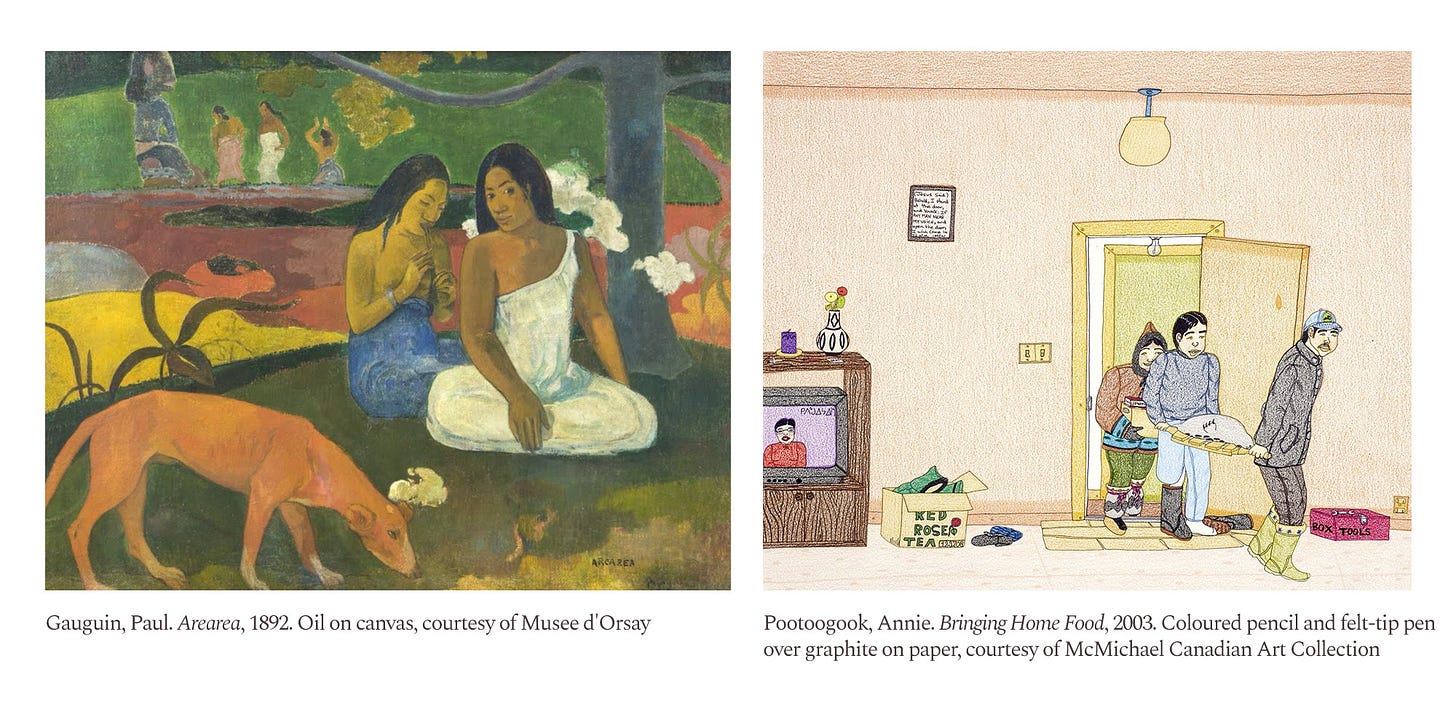

Romanticizing discomfort from an ivory tower while lots of people live in struggle has the leering quality of Gauguin’s primitivism, or the pompous utopianism of Captain Fantastic. Annie Pootoogook’s portraits of life in Kinngait, conversely, observe a “degrowthed” reality with neither a cynical sneer nor hyperbolic romance: sparse living (with key comforts), a harsh interface with nature, sharing resources rather than individual excesses. There is plenty of hardship, but perhaps also a sense of community and spiritual well-being.

It’s a confusing time to be alive. We are struggling with the hypocrisy of seeking a more natural life whilst dominating nature at every opportunity to maintain our comforts. We inhabit a bizarre middle ground: denial about our cyborg status whilst pining for a natural world that we probably don’t want, seeking naturalness in products that exploit the anxiety from our duplicity: organic beauty brands, nature retreats, shallow appeals to naturalism. I think this unpleasant hypocrisy is pushing people towards extremes, hitching their wagons exclusively to camp #1 or camp #2.

We’re going to have to accept that we don’t have the answers, and that hypocrisy is going to occur while we search for them. In my efforts to be more “sustainable”, I’m happy to make several sacrifices which are meaningful (I had them listed out but redacted as I felt like a douche) but which largely do not disrupt my privileged lifestyle. I have yet to be willing to limit travel or boycott AI (whose resource intensity is alarming). These two choices alone could outweigh the impact of my sacrifices.

People see hypocrisies like mine above and use them to deflate the arguments of behavioural change proponents, trapping us in a straw man (not unlike Father John Misty’s song) that we are merely virtue signalling until we sacrifice every comfort available.

And while the hypocrisy is real, I’m trying! And I’m 100% sure that my footprint is significantly smaller than the equally privileged folks who throw their hands in the air and say individual action is pointless.

3. All we do is play the victim.

I think that our continuity with other living things makes us tremendously anxious. If we felt that we had behavioural affordances and inclinations that weren’t all that different from the hopes and fears of other animals, we wouldn’t be able to have the food system that we have, for example. We wouldn’t be able to stand the idea of factory farms. I think it’s a sense of our own mortality and relatedness to other creatures that has resulted in this enormous overreaction that has produced the extremities of human exceptionalism, that make us insist that the rest of the living world doesn’t have agency, intelligence, or isn’t capable of suffering in the way that we are.

- author Richard Powers, from an interview with Sam Fragoso

Behavioural change proponents are trying to do what is within their control, and viable. On the surface, and thanks to the two criticisms above, these efforts can feel shallow, privileged, and pointless. They are easily mocked.

This is more of an anecdotal / vibes argument than a structural one, but people calling for behavioural change tend to be highly sensitive to this (I know I am). I think, resultantly, many play the victim card against those who diminish them, oppose their view, or choose not to match their efforts. Let’s be clear: none of us have the right to claim victimhood of climate change. Even for those who manage to exhibit zero-harm behaviour, placing oneself within the tragedy of nature is deplorable. No one wants to hear about it.

Regardless of what stance is taken on the correct response(s) to climate change, the first thing to be done is to embrace that we have lost the privilege to consider ourselves part of nature; we are the firing squad, the only choice is how often each of us pulls the trigger.

We Need to Sprint in Both Directions

To be clear, I’m not saying that behavioural change is the only path forwards. I just don’t believe putting all our eggs in the basket of technology is wise or necessary (nor is arguing for behavioural change alone).

Low-hanging criticisms are so easily lodged to sneer at proponents of degrowth. As a proponent myself, I find myself constantly succumbing to them. But isn’t considering technology as the only viable solution equally naïve?

We know the tech we need, but our ability to enact the structural shifts to adopt it is pure speculation, and feels at least as disruptive as widespread behavioural change. If continuing to cyborg the f*uck out on our mission to abandon the discomfort of earthly life does save us, we have no idea whether we’ll be happy when it does (doesn’t seem that way at present…). And of course, should the gamble fall short, we have no evidence that there is a new home for us. Even if there is, I’d rather drown in the rising ocean than live with BasedJeffBezos on Mars.

Perhaps we adopt humility while the e/accs work on the side of playing god. Perhaps by the time technology makes us the gods they so fervently wish to be, the rest of us will have learned how to be benevolent ones. Everything will balance out nicely.

If only we could be so naïve.

A few IRL examples of naïve, benevolent gods, minor to major:

My sister in Calgary regularly participates in Elbow River cleanups which, aside from being helpful, are probably fun.

My neighbour in Toronto leaves a box out on his porch for other neighbours to put their electronic waste. Acknowledging that most people are too lazy (or don’t know how) to properly dispose of them, he does it himself.

A company I worked for had a carbon rebate program for commuters: anyone who logged electric car trips, carpooling, transit usage, etc. were reimbursed per carbon pricing. Employees had the option to cash out or put the $ towards tree planting. The company trusted people to use this system honestly, and everyone I knew did.

Dalton McGuinty and Kathleen Wynne, successive liberal premiers in Ontario, led the Coal Phase Out from 2003–2014. This was one of the largest climate action policies in North America, resulting in the closure of all coal-fired power plants. Perhaps this was a less volatile era, but I still can’t imagine how delusional they must have been casted as by opponents of this effort, and probably, at times, how delusional their own efforts felt. Presently, 93% of Ontario’s electricity generation comes from low-carbon sources, with over 50% from nuclear <3 <3