you are already a world builder

Elicser Elliott | Neglected Nostalgia | BAND Gallery /// but also Kent Monkman

**images courtesy of: artists featured, Elicser Elliott, Kent Monkman; gallery, BAND Gallery**

Elicser Elliott

Neglected Nostalgia

BAND Gallery

Curated by Nehal El-Hadi

June 20 - July 27, 2024

“A good movie is three good scenes and no bad scenes.”

- Howard Hawks

I rarely start writing a story with more than a handful of key scenes or moments in mind. Writing is the tiresome work of digging tunnels between these points; editing is the backfilling of tunnels that went astray until the path feels (jaggedly) direct; insecurity is repeatedly circling the path to figure out why it exists, whether it even should. Throughout the process, the original moments stand tall as guiding beacons.

These “pillar” moments tend to be sourced IRL, but along the way their edges get softened, blurring with the surrounding fiction, to the point that they are no longer distinguishable from it. I squeamishly began to realize that this process is altering how I remember things.

Is it better to falsely memorialize the moments, or to risk losing them?

Elliott, Elicser. Rude boy in the white slippers. 2024, Acrylic and crayon on panel board, BAND Gallery

In Neglected Nostalgia, artist Elicser Elliott passes formative moments from generations of his family lore through the filter of his own memory, resulting in a new set of images. Colourful streetscapes of Saint Vincent, where Elliott lived, are often towered over by larger-than-life human figures, like lumbering giants in a fairy tale. The figurative style is familiar to those who have seen Elliott’s iconic murals around Toronto.

Some figures loom extra-large, while others are proportional to their surroundings, causing the latter to feel like mise en scène. This parallels how our memory selects random elements—a song, a feeling—to occupy disproportional space, while others are blurred or even forgotten.

“…trying to exactly talk about the place that I’m slowly forgetting”, said Elliott, during his artist talk at the exhibition opening. Exactness might have been a throwaway word, but I nonetheless latched onto it. For this is an artist who understands that exactness in memory is impossible.

Left: Elliott, Elicser. Jo. 2024, Acrylic on panel board, BAND Gallery

Right: Elliott, Elicser. Ramon. 2024, Acrylic and oil stick on panel board, BAND Gallery

J. Robert Oppenheimer holding a goat beside Elliott’s mother as a child, flying a kite; a family lounging on the beach like resting giants in Shadow of the Colossus; faded buildings stacked atop each other as if documenting a town’s development. Moments are handled like Lego blocks, but play does not make the practice unserious. Through world building, Elliott revives memories which were not his own and would otherwise be lost. A pastiche of memorable bits arrives at something concrete to hold on to, and by doing so he acknowledges how all of us treat the past.

Elliott, Elicser. Jackie, Jo, and Oppenheimer. 2024, Acrylic and crayon on panel board, BAND Gallery

One only has to slog through a few art exhibition statements to know that artists are tasked with DECONSTRUCTING and RE-CONTEXTUALIZING the world around them. Curatorial texts love beating these verbs over our heads, but they are far from exclusive to the role of the artist. Elliott actively applied a transformation that time forces upon all of us, whether we consent to it or not.

The way we remember relationships is a classic example. Emotions in the present violate our memories, altering them for better or worse. In the aftermath of losing someone, their images take up more space in our memories, dominating the landscape, their voices carrying further. Colours of scenes they were present for are painted by the triumphs or sufferings which succeeded them. Once the violence has passed, we feel that we are finally looking back on our history objectively. But how could our memories have passed through such turbulence unscathed?

Elliott, Elicser. Pasteleria (baking crayons). 2024, BAND Gallery

“In a history of colonizers, where are our histories?” said Elliott. “[An artist residency] gave me the license to make it up. You don’t have a history, and that’s okay—reimagining is alright. [I thought of] great kings and queens of the West Indies. Back then there would be a woman that was captain, that sailed the seven seas and was a pirate. [You can] take a little bit of information and then re-sculpt it into this whole other idea.”

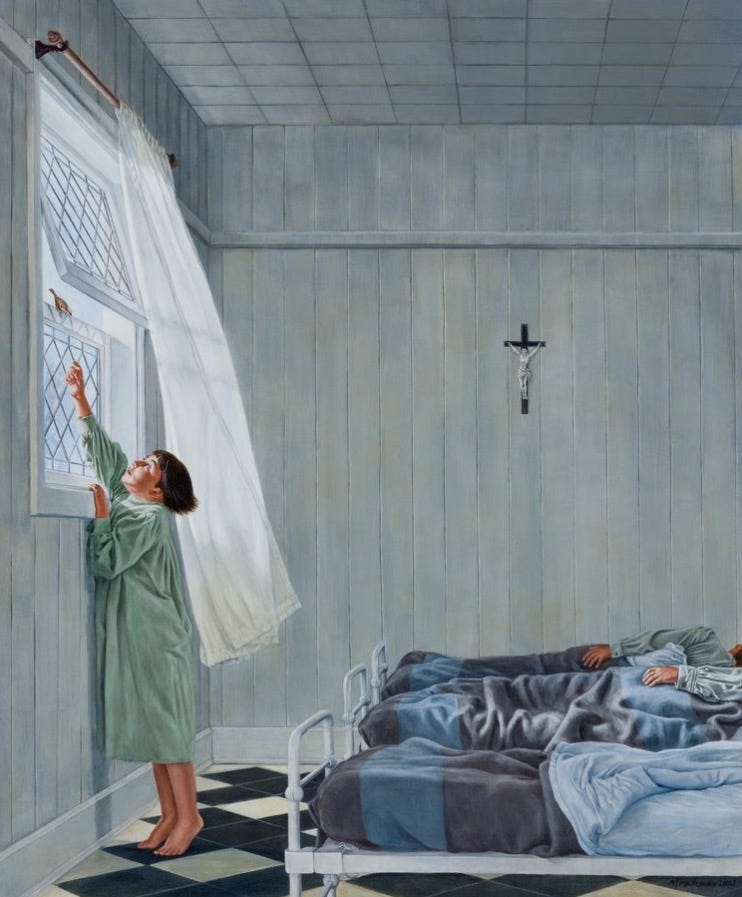

Elliott’s words remind me of one of Canada’s most interesting visual artists, Kent Monkman. A member of Fisher River Cree Nation, Monkman paints dramatic scenes of colonial violence against Indigenous people. In many of his works he overturns the narrative, portraying a history where Indigenous traditions prevail, while maintaining a painting style common to 19th century Western European art. With a sense of levity and a wink, his works are playful (but very serious) explorations of personal and cultural memorializing via world building.

Monkman, Kent. Study for Cease and Desist. 2022, Acrylic on canvas

From Kent Monkman’s interview with The Met on December 29th, 2023:

“I became very interested in European painting when I realized that there was an opportunity to paint Indigenous experience and histories and kind of authorize them into this art history that pretty much neglected our perspective.

I wanted a persona to really reflect our point of view at the time that the colonial policies were beginning… So I created Miss Chief Eagle Testickle to offer an Indigenous perspective on the European settlers and to also present a very empowered point of view of Indigenous sexuality pre-contact. We had our own traditions of gender and sexuality that didn’t fit the male-female binary.

Miss Chief is a legendary being. She comes from the stars. There’s something very liberating about having an alter ego because it allows me to kind of act in a way different than I would normally act.

Miss Chief brings something to my practice that I didn’t have as just a painter. She allows me to be more playful in my work because she inhabits a sexiness and sassiness. She allows me to lighten how I treat sometimes very dark subject matter because I’m looking at effectively a genocide.”

Monkman, Kent. Compositional Study for They Walk Softly on This Earth. 2022, Acrylic on canvas

Historians are quick to warn against taking their work as gospel. They know better than anyone that we have little more than a jumble of narratives and artefacts piled atop one another to draw outlines from. Small discoveries in the present sharpen the contours; larger ones alter the entire structure, forcing us to draw new lines. Dominant narratives prevail until our notion of dominance changes. Lines of fact and fiction seem hopelessly intertwined.

We roll our eyes at the friend who compulsively boosts a story that we were there for and know went differently (but do we really?). Forgetting or misremembering our past is a source of embarrassment over our failing faculties, an insecurity which many products feed on. We are encouraged to honestly reckon with our past, to meet our traumas (and otherwise) head-on. And no doubt, there is a time and a place for taking history seriously. But history too easily impacts a present in which we are so much larger than our stories. It is possible, and strangely comforting, to simultaneously hold stories sacred and strip them of their austerity, accepting that they can’t be relied upon. It doesn’t take an artist to sculpt the past how we please, pretty up the picture. It will look different tomorrow anyway.