art that feeds itself, nourishes us

exploring artworks that transcend their medium and live on inside of us.

images courtesy of,

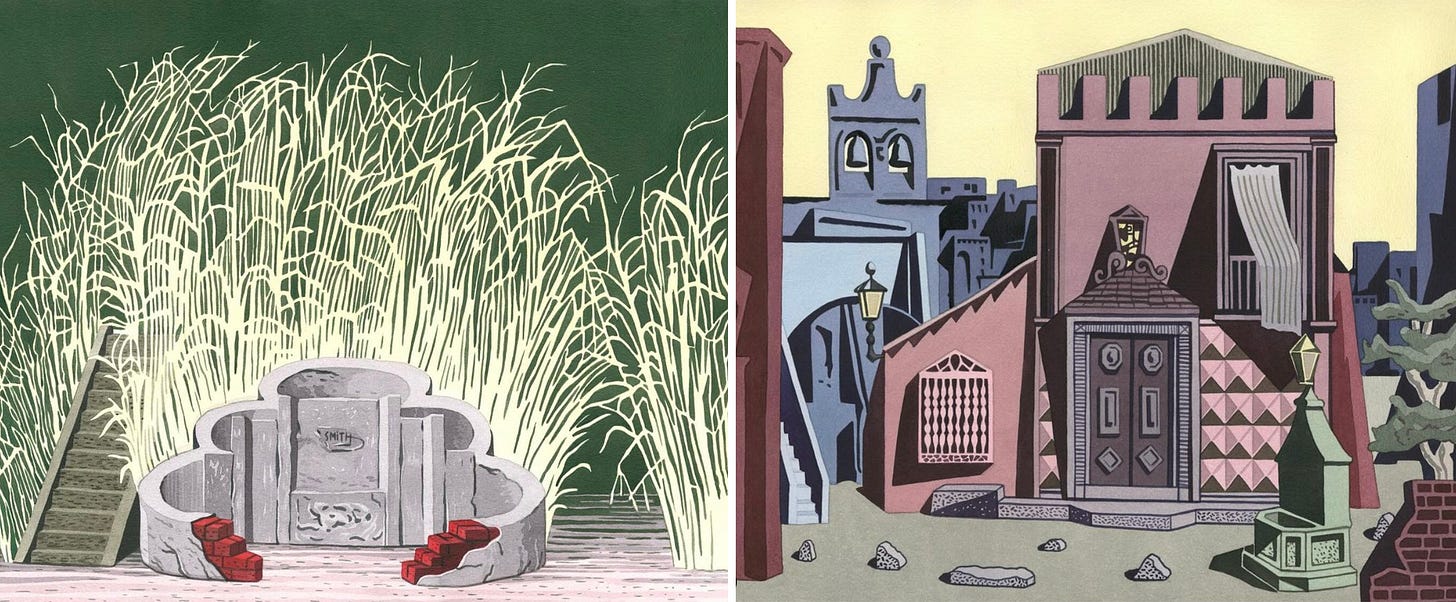

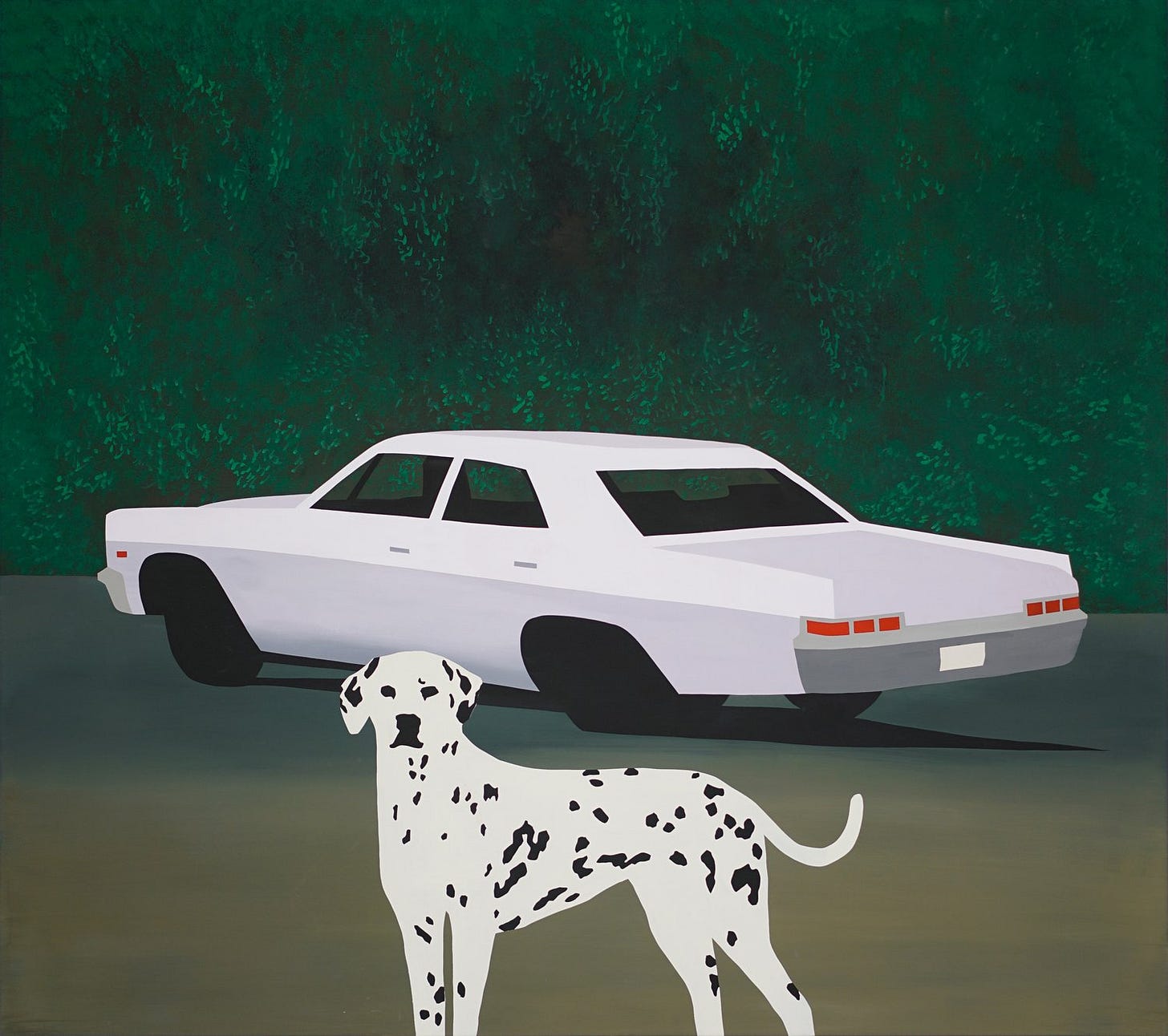

artists featured: Luke Painter, Dan Climan

gallery: Patel Brown

In this essay, I talk about works of art that transcend their form. That’s a loaded phrase, but what I refer to are those artworks that live on inside of the viewer, long after they’ve experienced the art. Or, vice versa—the viewer lives on in the work. Whether the confine is a canvas, screen, or set of pages, the art finds its way beyond.

I would LOVE to hear about some artworks—books, video games, art objects, albums, or otherwise—through which you’ve experienced this transcendence.

There are certain works of art in which the universe presented is so engrossing that its subject matter, or raison d’être, becomes secondary. Some examples where this has occurred for me:

The indulgent length of Underworld by Don DeLillo had me dozing off and skipping passages, but its setting has long lived in my conscience; if anything, my hazy, detached reading of it enhanced the immersion amongst lost souls in a gritty, postwar New York.

In Notting Hill I was quite indifferent towards William Thacker winning over (the toxic) Anna Scott—I simply wanted to inhabit his charmed, bumbling existence.

Space is Only Noise by Nicolas Jaar continues to sweep me into some haunted grayscale of masquerade balls and abandoned playgrounds—neither of which are explicitly suggested by the work.

In each case, there came a moment where the maker no longer had to justify their universe—through a mysterious spell which only art can cast, they gained my involuntary immersion.

For me, this transcendence of form surpasses art that triumphs at an intellectual or emotional level. Art that achieves it stays with me permanently, often acting as a filter through which I frame and process my own experiences.

This type of resonance is unpredictable and highly personal. It requires an invented universe to feel more compelling than my own. It also demands absence; enough must be unsaid, or unstructured, in the art to leave space for me to inhabit it. Conversely, art with many parameters (an elaborate plot, a pointed agenda) usually strikes out for me in this transcendent category, no matter how successful it is otherwise. I cannot let the universe exist outside of those parameters.

I shared examples of this experience for literature, film, music—not visual art. How does transcendence of form occur in a quiet gallery space, with fluorescent lights illuminating an ambiguous art object? I will go out on a limb and say that most readers can recall the experience I’ve described with a book, album, or movie / show (perhaps all), but would be harder-pressed to recall the same from an art exhibition.

Perhaps these (relatively) newer formats simply have more, or better, tools for creating immersion. But I think there is another factor at play.

Having viewed at least one art exhibition per week for the past few years, I’ve felt that the overwhelming majority (call it 3/4) of the art was deeply concerned with its purpose. Rather than existing for the sake of itself, it sought after an expressed goal which was often unclear by just looking at the art. Lacking an exhibition text or the artist on-site to explain it, much of the art did not seem created to support itself.

I should note that many of these efforts were successful—a few of which I have covered in past essays. They had ambitious goals which demanded explanation, and paired with the necessary context, were brilliant and enlightening. But these instances were the exception, not the rule. What remains is a whole lot of art that is not functioning aesthetically or intellectually. Maybe this happens because too many artists are focused on the latter.

I want more of visual art to not feel the need to explain itself. I want more art exhibitions to embrace artists as stylists, or to feel comfortable trafficking in vibes. There is a sense that aesthetic ambitions are trite, or that aimless exploration prevents artists from being taken seriously. But having met so many people who can’t (but wish to) connect with visual art, I suspect a lack of immersion, rather than seriousness, is the problem.

There are countless visual artists who have constructed universes which stand firmly on their own. I’ve featured works by the artists Luke Painter and Dan Climan throughout this essay. These are examples of extremely effective visual communicators who assert image as a language. I haven’t expended a single letter on them until now, but I suspect, from a handful of images, you were able to connect with the work.

Not that one can’t write about their practices. In Climan’s work there exists a nostalgia for a simpler, more intimate world, in tension with the anonymity of modernity (which feels Hopper-esque, but magically not). In Painter’s, a deep fascination for the objects underlying the visual data we mindlessly consume. But it feels, independently of these explorations, that both artists have constructed universes they adore. Their sincerity for and immersion within them are infectious.

Both of these artists are interested in a bygone era of mid-century cinema. In the decades following the advent of sound film in the 1920s (known as the Golden Age of Hollywood), the theatre and photograph as narrative and visual forms took a back seat. With the demand for the TV spot over the print ad which followed, static images seemed threatened by obsolescence. In Painter’s most recent exhibition at Patel Brown in Montréal, Moving Images, he gives reference to the tools and techniques of set design and animation—both essential to bringing static images to life. By placing them within a painting, and manipulating them in absurd ways, Painter distills these moving images we revere into a set of techniques and inanimate objects. Then he deftly constructs a compelling universe around them. Climan’s carefully-selected scenes are another distillation, from cinematic universes to a handful of essential images. In both cases, the artist asserts the importance of static images amidst the immersive, narrative mediums which depend on them.

From Painter’s maximalist world, I somehow crave more data—to know what’s behind that door, up that staircase—moving through the images in my imagination like a choose-your-own-adventure character in a campy house of horrors.

From Climan’s, I crave for my own life the intimacy and intensity that each scene contains. Each moment, through the careful selection of focal points, omissions, and subtle gestures, feels climactic—a short story in of itself. I reflect on my memories and recognize them rarely as a film or a novel, but a handful of pivotal images from which a universe unfolds.

In both cases, I am left unguarded, unthinking, at the makers’ will. This is a rare achievement in visual art, but maybe it doesn’t have to be.