Devon Pryce isn't seeking answers

The art of letting a story breathe

“Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.”

— Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

You don’t need my reporting to know that the millennial habit of self-analysis is alive and well.

Perhaps you’ve heard, or participated in, the conversation that occurs between friends in any urban space with a commercial espresso machine. On the surface, a friendly catch-up. One level deeper, a stilted exchange of self-reflections in which the listener’s task is to nod respectfully (we listen and we don’t judge). Life events are recanted not as the narrator’s embodied experience, but from the POV of an analyst over their shoulder. Stories are phrased and remembered as experiments in which subjects either succumbed to or overcame their patterns.

Start listening for it and you’ll hear it everywhere. Probably from your own mouth, too. In early April, I was catching up with a friend who I hadn’t yet seen in 2025. He asked what I’d been doing. My most honest response would wax romantic about writing breakthroughs, movies I had seen, cozy hours by the fireplace. Instead, it came out cold and flat. Something along the lines of, I’ve been writing and watching movies. Crazy how little else I have to report after all these months. I need to get out of the house more. A therapist would no doubt have a satisfying explanation for why I reported the latter, which I could append to a list of behaviours that also includes my tendency to socially hibernate. The cycle of analysis continues.

I’m sure our generation’s heightened self-awareness, however indulgent at times, is a net-positive. But perhaps the common language we’ve adopted, which favours prescribing and diagnosing (both important), has stripped our past of (also important) narrative quality. Maybe our analytical approach to self-reflection is a path of least resistance that leads us to neglect the myriad personalized, murkier, and more challenging (but perhaps rewarding) expressions of it — one example being art. This isn’t to say people should ghost their therapist and channel their trauma into a drip painting; I’m merely wondering how often, and carefully, we should evaluate the filters through which we process our past.

Perhaps your filter arrived in a golden basket via a Podcast ad with a promo code for BetterHelp, and maybe that’s working really well. But if we believe in the infinite uniqueness of the individual (we don’t have to), the widespread adoption of any sweeping method or language of self-reflection is worth challenging.

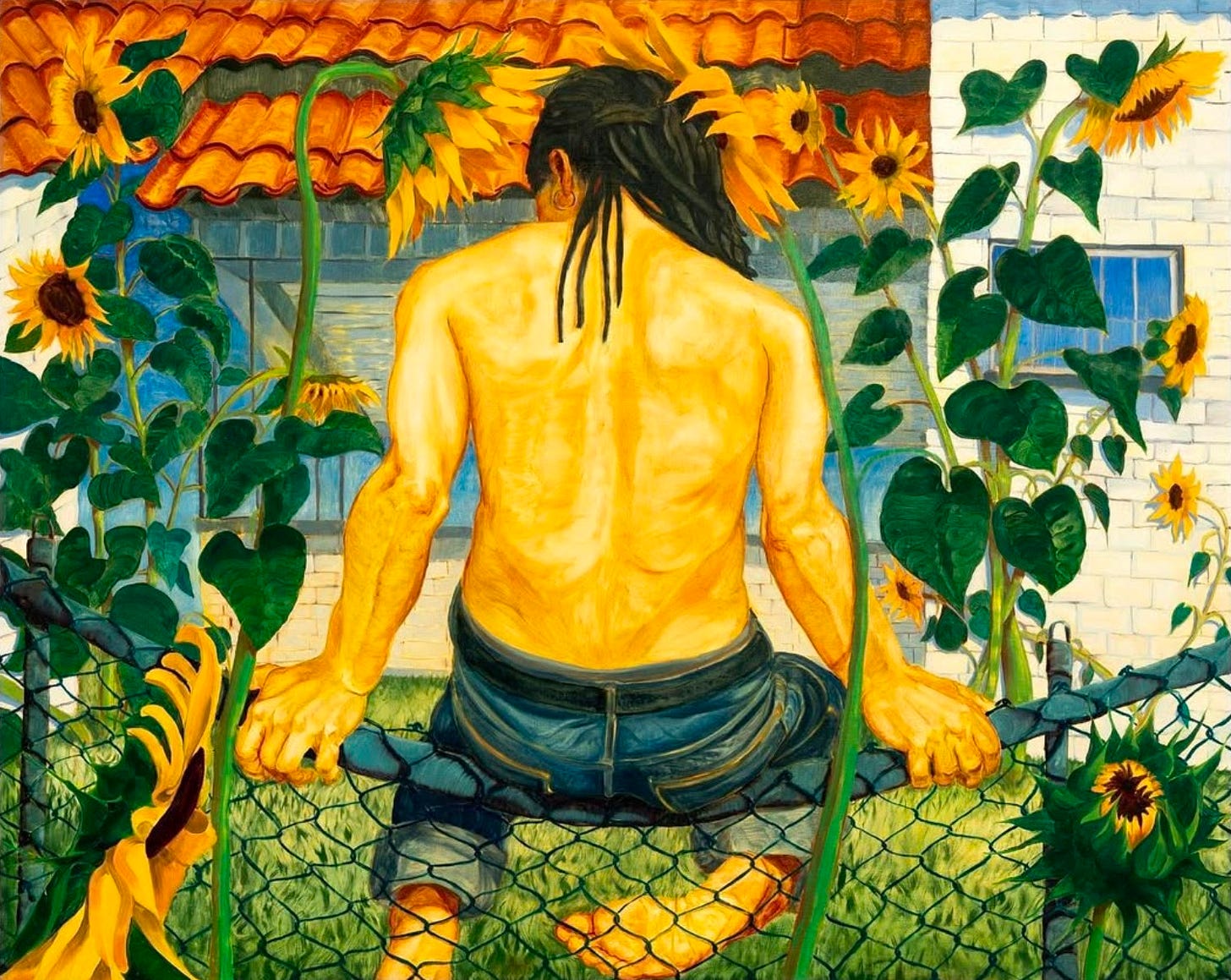

Devon Pryce’s portraits are an example of self-reflection through a less prescriptive, more personalized lens. I knew I would write about his work when I realized I could hear the painting at the top of this letter, titled Headlamp: the spurts of a sprinkler, a creaking fence, cicadas, a gentle breeze. His images contain a deep intimacy with the subject (often the self), and a gift for cinematic, harmonious framing of a figure within their surroundings. The focus on exposition rejects the notion that with enough self-work, curation, boundary setting, etc., the vacuums we cultivate might become immune to the prickliness of the world. Nature abhors.

Aesthetically, Pryce’s work is deeply gratifying — the pastels and rippling fabrics, the coolness of his subjects. I could stop writing and drop a bunch of pictures, which I'll do in a sec, and you’d recognize that too. But his narrative exploration of self is the grounding sentiment that holds you. It places you front and centre to a moment of processing, where analysis gives way to vivid experience. This is close third-person, in literary terms: no over-the-shoulder analysis detected, despite an outsider view. An exact likeness does not always equate to successful portraiture; the work is in finding space for the sitter’s story to punch through.

Pryce experiments with scale, particularly with bodies, in a way that feels visceral. When you walk into a room and everyone turns to look at you, do parts of your body enlarge? Do you look down at your hands and they are the hands of a clown? Do you fixate somewhere in the mirror or when looking at an image of yourself? We can strip these experiences of colour by labelling them a self-esteem issue, or we could do our best to express the lived experience. The way my face was expanding like a balloon from the inside out. The uncertainty of that moment, how it made me feel like I was two different people in one body. Whether moments of duality, tension, balance, despair, each is embraced as part of a narrative that keeps unraveling.

The expressions of self-awareness that serve a person may not always feel easy or natural. Despite current trends and this manipulative ad campaign, the process need not always default (or be exclusive) to therapy. For me, it’s putting sentences together, then releasing and forgetting about them. For Ryan Van Der Hout, in another letter, it was documenting a past self in glass and the liberation of shattering it. For Summer Wagner, it was having a seance, of sorts, with your shadow. These are metaphors of self, processes of self-reflection channeled into art — but they need not result in art. For someone else it might be drinking several pints and telling a story. What’s important, in each of these processes, is that the goal was one of exploration. Relying on a language unconcerned with solving a problem. Often, the expression was so personal and felt that it wasn’t worth posing a question. We, as the listener or viewer, had the privilege of experiencing the narrator’s life the way they did.