Excuse me, I ordered my art with 1 tsp politics

Not the other way around!!

Good morning! Today, I feature some overtly political art (love it or hate it) and muse on the direction art might be headed w.r.t. politics. And whether we have any right to complain about art trends. Oh and I respond, after much delay, to The Painted Protest.

Show don’t tell is a maxim for writers that trickles in to every art form. Artists are broadly advised to explore rather than instruct, for art that focuses too much on the latter risks lacking depth, or imagination, or both. Artist statements love verbs like inquire, re-contextualize, interrogate, subvert, transcend — language of experimentation which invites the viewer into the artist’s open exploration, taking us one level deeper rather than forcing a conclusion upon us.

Of course, no creative maxim holds perfectly true. There are successful works which mostly tell, or mostly show, and either can be saying absolutely nothing, or a lot. They also have no obligation to be saying anything. Sigh, headache. Anyway, I’m interested in this spectrum of verbs — show, explore, inquire ↔ tell, instruct, declare — because I’m predicting, in our politically charged moment, for the art mainstream to move away from the former and towards the latter. If you think art, for the past while, has already been in a category of tell, instruct, declare… I disagree! Read on.

For the last while, contemporary art has been obsessed with identity. And while there are many examples of identity-driven works that tell, instruct, declare, the dominant mode that I have witnessed leans in the other direction of this spectrum, towards self-exploration and introspection. Identity is complicated, people are unreliable. Accordingly, these explorations tend not to result in hard conclusions — they tap into the artist’s sense of self and rest there, often in ambivalence. These works are political, but the politics usually extend as an inference from the work, in a decoupling that often feels quite intentional.

It is often argued that this category of work does not “achieve” much. Or, that explorations of identity (particularly certain identities) are automatically credited despite being shallow or derivative. Or, that artistic merit had been sacrificed for a set of values to be checked off like a DEI audit. These sentiments culminated in the popular Painted Protest essay by Dean Kissick. I agreed with some of its criticisms, but feel that the author lost the plot in his romanticization of a bygone golden era of art, which coincidentally aligned with his good ol’ days. He elevated art to a (falsely) sacred status, suggesting a period where it was siloed off from the facts of the world, where artists “were researchers who were never expected to come to any conclusions”, and “had the freedom of absolute purposelessness”. In the same breath, the essay laments identity-driven art for “offering fantasies of resistance, but having little to offer in terms of genuine, substantive social change or artistic experimentation.” So do we want art with purpose, or not? Maybe the author just didn’t appreciate this category of purpose.

The piece felt more like an attack on identity politics than art. If so, the attack was well-timed. Identity in art (and everything) was a trend that we already recognized as decadent — as trends become, towards the end of a cycle — but that also held meaning for many people who don’t look or think like Dean Kissick.

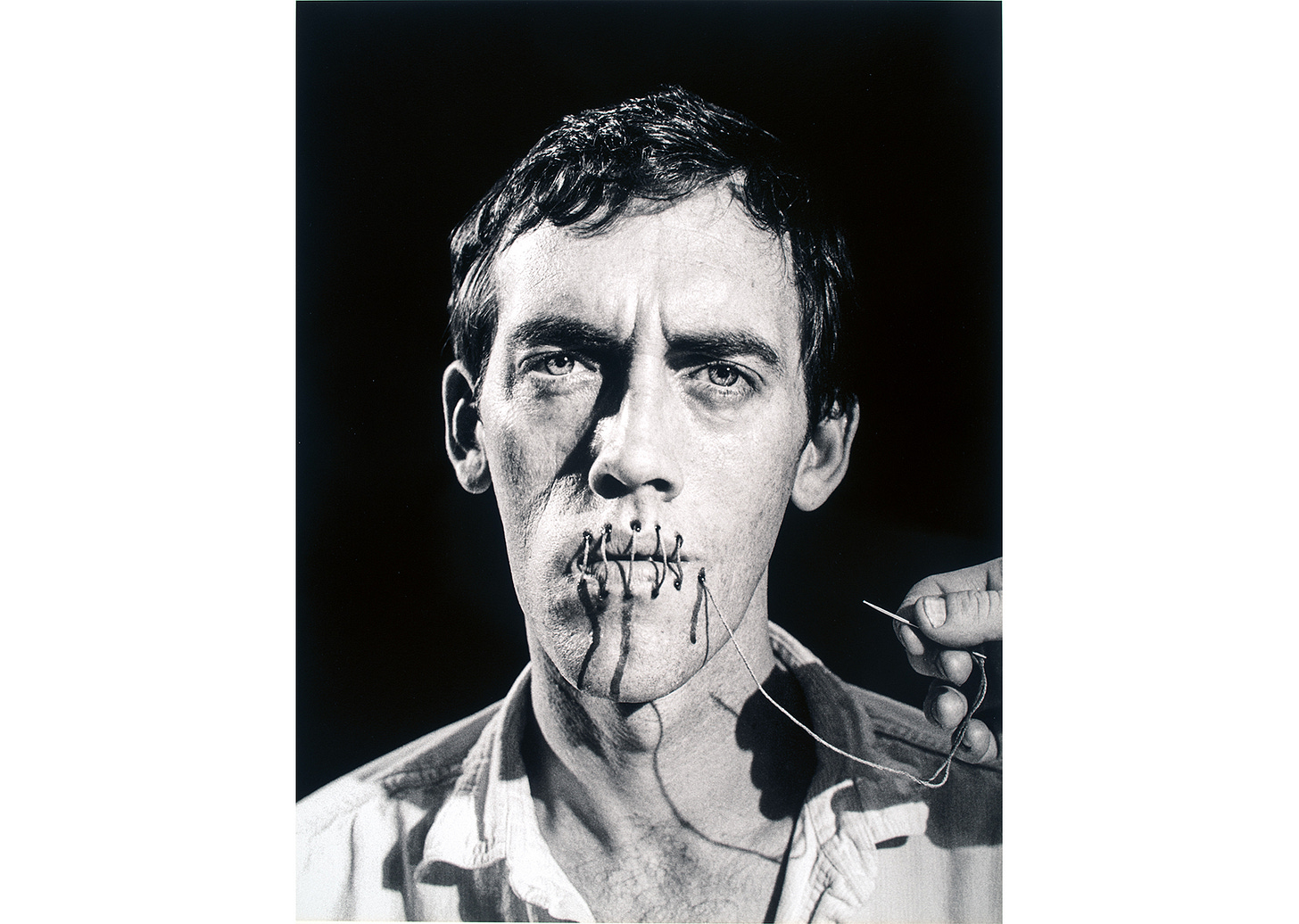

But back to my prediction for art. The decadence of identity politics prompted the cultural backlash we are witnessing in real-time. Even in the lefty art world, we’ll likely see fewer explorations of identity as a result. Arts-oriented people are not comfortable right now (are they ever?) and politics is the topic of the hour. I suspect, as a result, we are likely to witness a shift towards less nuanced, more overtly political art, which more closely aligns with the verbs tell, instruct, declare. The type of art I’m featuring in this essay. A shift from ambiguity and introspection towards prescriptive demands and clear delineations of right and wrong. If you felt that identity-driven art was already too political in tone, this might be bad news for you.

If I am right about this, my gut reaction is not one of excitement. Alarm bells start going off in my head when the political or ethical motives of art are clear from a distance. But this is a privileged outlook on the role of art from the comfort of my stable environment. To lament a shift prompted by genuine sentiments of grievance that might not apply to me would put me in the same camp as Dean Kissick (no thank u), neglecting that for many people, to not speak, or to speak too quietly, is not an option — it’s not something they considered.

Another response to IRL events, which we might also expect, is the surfacing of the category of art I tend to most enjoy: a burrowing away from real life into the soul or imagination, particularly towards an artists most absurd, escapist corners. Dadaism, for example, emerged partly as a reaction to WW1’s failure of rationality and political systems. Instead of prescribing solutions, Dadaists were deliberately chaotic. They refused to offer clear meaning, instead exposing the absurdity of political and social structures through randomness and irrationality. I’m sure I’ll write more about Dadaism in another piece. But my gut feeling (and my algorithm) tells me that absurdity is not the direction we are broadly headed. Should my prediction prove true, rather than criticizing the lack of a more “nuanced” response to current events, I will remember that I have the freedom to make art which reflects my own grievance.

And this prompts a question about criticism more broadly: should we be disparaging the results of spontaneous creative and intellectual acts, and how these individual results bubble up to wider trends? Should criticism extend beyond the attempt to digest and interpret? Today’s essay seems to be suggesting that no — it shouldn’t. But I’m no critic. If art doesn’t interest me, I move on. Maybe a critic would say: why don’t you give criticism the same leeway that you give art? It, too is a creative and intellectual response. Fuck, I’m not educated enough to be writing this paragraph. Future topic.

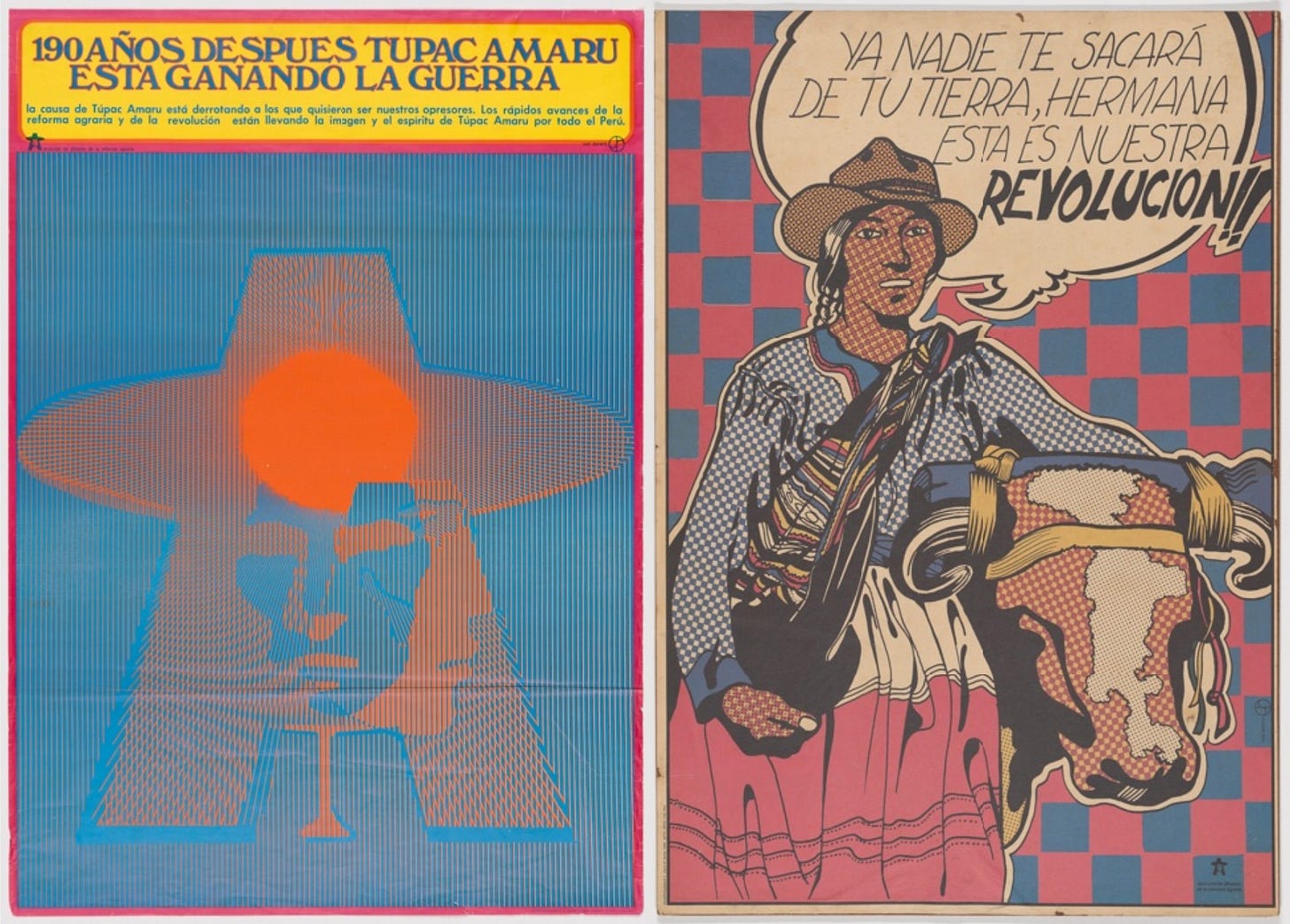

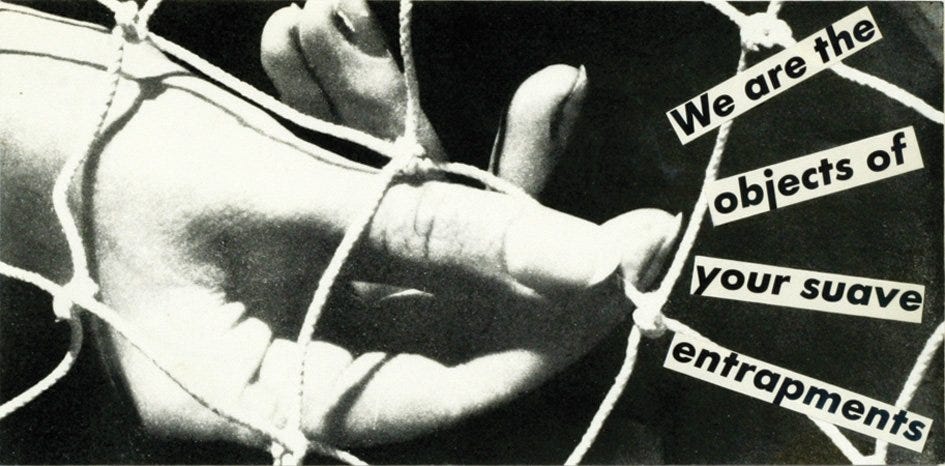

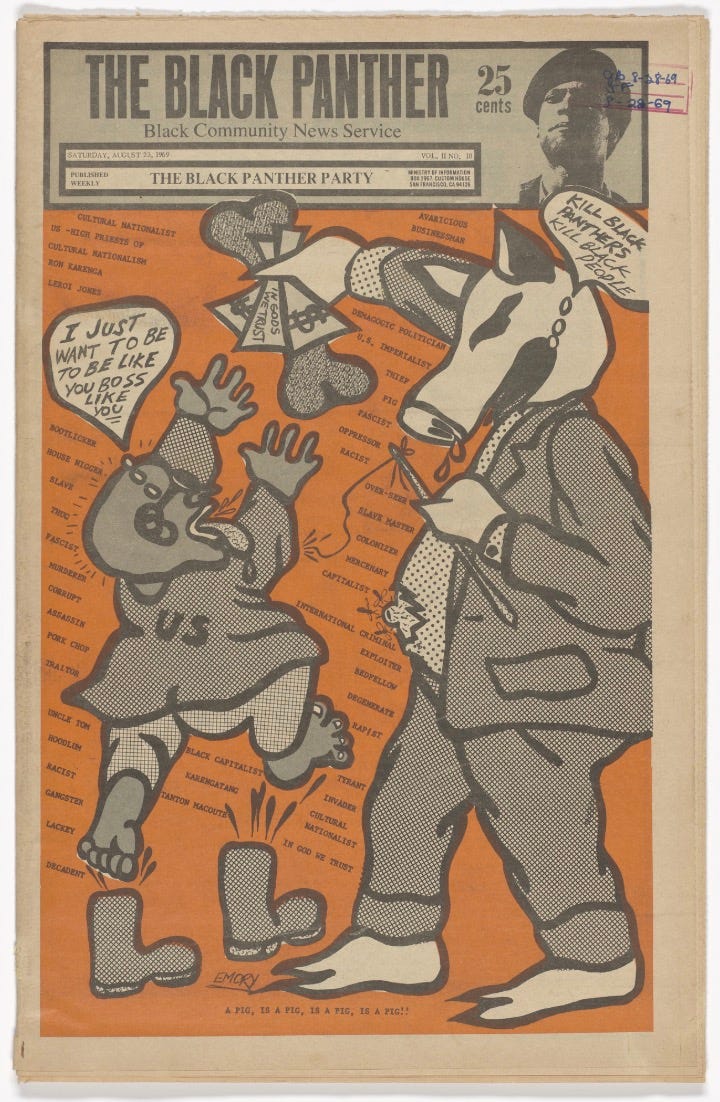

I’ll be watching closely to see which art forms rise to prominence in 2025. I’m wondering if more works will emerge which look like Jesús Ruiz Durand’s or Emory Douglas’, borrowing from pop art techniques to push overtly political, propaganda-esque messaging. Or if we will see more critical, declarative text-based art, per the likes of Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger.

Neither of these are forms I instinctively gravitate towards. But should the art mainstream favour more on-the-nose formats, at times perhaps feeling like a mouthpiece for the politics I am trying not to think about, I will remind myself that art (like politics) is not a walled-off playground, but a squirming, imprecise, response to what’s happening on the ground. I’ll follow along wherever it goes.

Thanks for reading! There are a lot of opinions in this essay that I would love to have challenged. Please let me know how you feel in the comments.