How visual art makes me feel less insane

Notice the rope, give it a yank.

What have I been preoccupied with lately? A thick piece of rope dangling from the tailpipe of a parked car I walk past most days, on my way to the gym. I’m not fascinated by the rope, per se, but the temptation to pull it. It is dying to be pulled. What might be the result? Will the car explode? Will a never-ending line emerge, as if from a magician’s hat? Will a prize be waiting on the other end? Each lap to and fro lends plausibility to these conclusions and many more. Invariably, obsession wins me over. I crouch by the tailpipe and yank on the rope. Out it comes, about eighteen inches long, its far end matted with grease. I carry it home and store it in a shoebox containing several other objects that have been the subjects of recent, inexplicable obsession.

How did you respond to the latest impulse that came knocking at your door? Did you study it surreptitiously through the peephole, before leaving it to wither on your front porch? Did you let it inside, only to ridicule it with labels borrowed from the language of affliction? That’s my OCD kicking in. Ignore [X] I’m literally insane. [Y] is my autism. To unabashedly embrace obsession is to risk being seen as an indulgent lunatic, detached from “what really matters”.

Cast in a more generous light, however, it is to let yourself be an artist.

When artists talk, often at length, about “process”, that holy concept, they are referring to a set of ever-changing rituals that minimize interference between the mysterious void from which impulses arrive, and action. How these rituals manifest becomes a proxy for the artist herself. In Luca Soldovieri’s practice, it involves grinding niche objects (dead moth, speedometer needle, receipt for ½ dozen tulips) into a fine dust to be categorized meticulously and later used as illustration media. In Azadeh Elmizadeh’s, it involves hiking into the rugged mountains surrounding Tehran, imprinting blank linens with the texture of the landscape before using them as a painting surface in her Toronto studio. The more compelling the artist’s work, the more sacred their process tends to be, the more likely they are to have followed their instincts to the furthest reaches. This is why AI—a deliberate abandonment of process—does not make worthwhile art. It can only displace the work of artists who overlook process, who create art purely with a “viable product” in mind, whether commercially or technically. Per E.H. Gombrich’s popular (and oft-misused) dictum, “There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.”

All art forms are deeply intertwined with process, yet I consider visual art to be the most (or, perhaps, the most conspicuously) process-driven of the bunch. I suspect this is due to a combination of the tactility of the final product and the marketability of the visual artist’s process: we often expect their hand to be visible in the finished work; we love to see footage of the messy, neurotic, nitpickiness of their studio practice. This intimacy with process, and tolerance for unpolished work, tends not to be so widely (or publicly) embraced with writers, filmmakers, musicians, and so on. Perhaps a positive, even necessary outcome of AI is that the deeply human element of process will become more apparent in the finished work of all mediums.

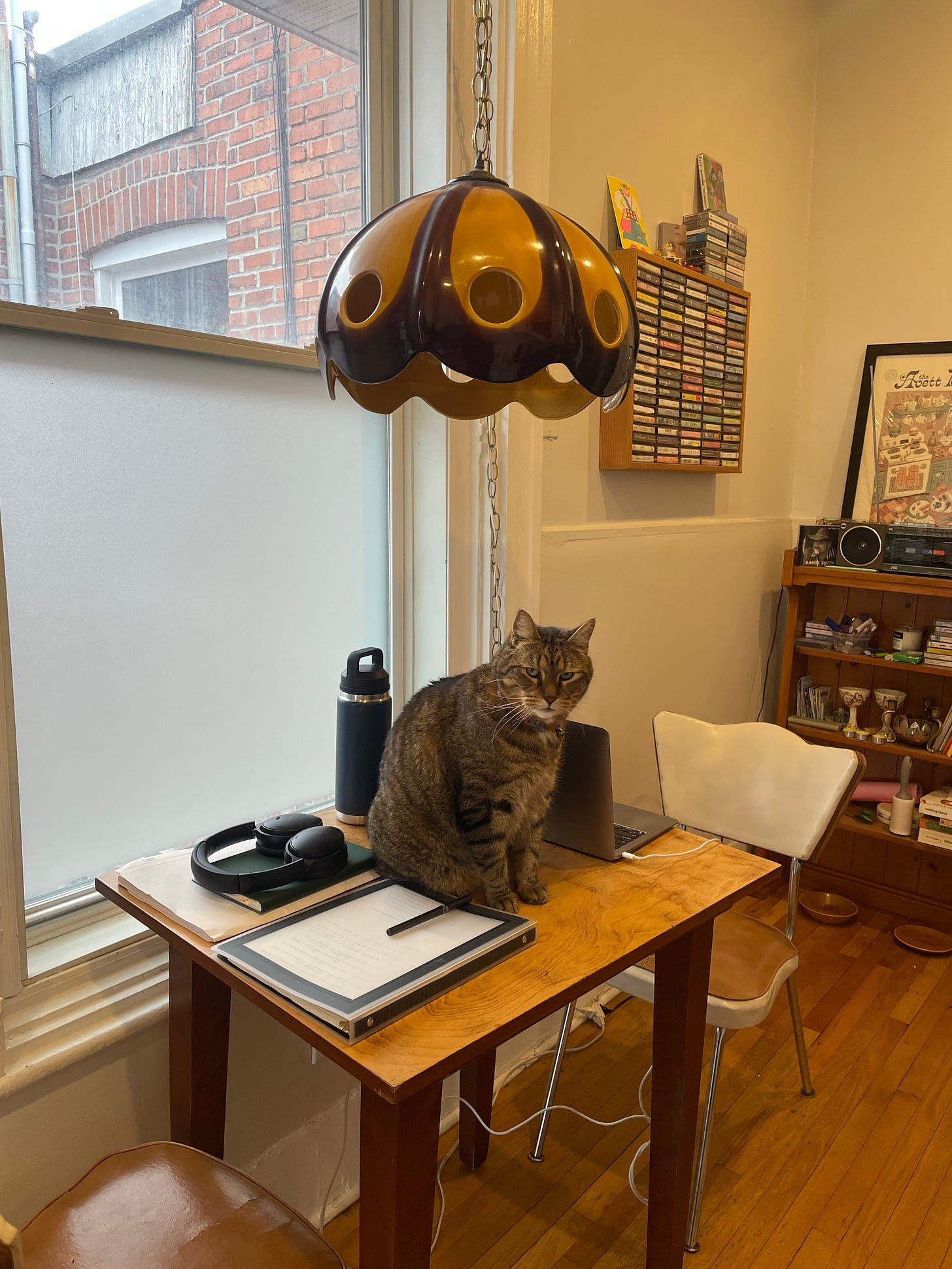

I’ve been blessed, over the years, to have hundreds of conversations with visual artists revolving around their process. Each has helped me accept the excesses of my own writing practice, which includes—as an example amongst many—the recurrent scouring of past weeks’ worth of iPhone notes, journal entries, photos taken, posts saved, mysterious shoebox objects, etc. for thoughts, descriptions, and ideas, all of which end up in “Sentence Master.xlsx”, a spreadsheet containing thousands of rows of sentences and paragraphs, categorized extensively with tags and attributes. Years ago, when the impulse to populate this spreadsheet would arrive, I ridiculed it with something along the lines of, Hemingway climbed mountains, shot zebras, impregnated women, and wrote several books in less time than you’ve spent tending to a spreadsheet mining the drudgery of your life for inspiration. But through hearing so many other artists describe their impulses with pride—they often aren’t sexy or marketable; they are what they are, unanalyzed, unquestioned—I have come to understand that the dedication to such pursuits is the truest, and perhaps only, measure of artistic fulfillment.

The next time an impulse comes knocking, you might welcome it as a long-awaited guest. Maybe it manifests as re-organizing the storage room, curating a niche playlist, or spending an afternoon scouring the city for a specific brand of Korean fermented chili bean paste (Doubanjiang). Whatever the rope might be, notice it. Give it a yank.

Related Reads

The work of Luca Soldovieri:

The work of Azadeh Elmizadeh:

Some notes on my writing routine: