Leaving the White Cube

A petition for more confusing art in public spaces

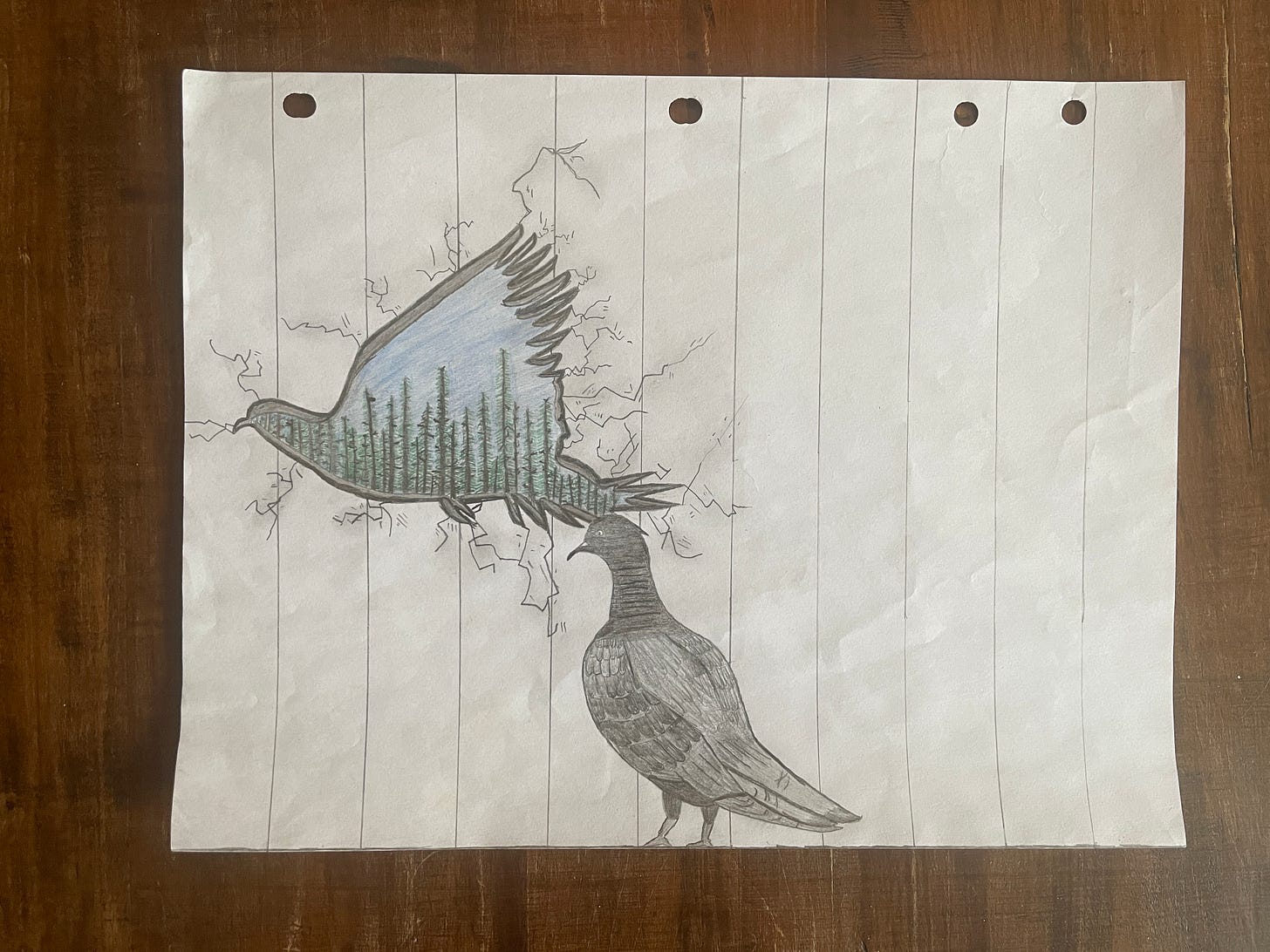

It should be clear by now that I have a sort of religious fascination with gallery spaces. A holy signal arrives in the form of a crisp installation shot via newsletter or Instagram and I make the pilgrimage to various inconveniently situated white rooms across the city. If art could be considered god (lol), my relationship began as a devout believer: I came for the art, nothing more. Gradually, my participation became more casual — what we might call culturally religious. I came for the church community, the vibes, the ritual. Sometimes, I simply had nothing better to do on a Saturday. The art was always there, and in some cases, it was the main attraction. But most of the time, the art and gallery experience were one and the same.

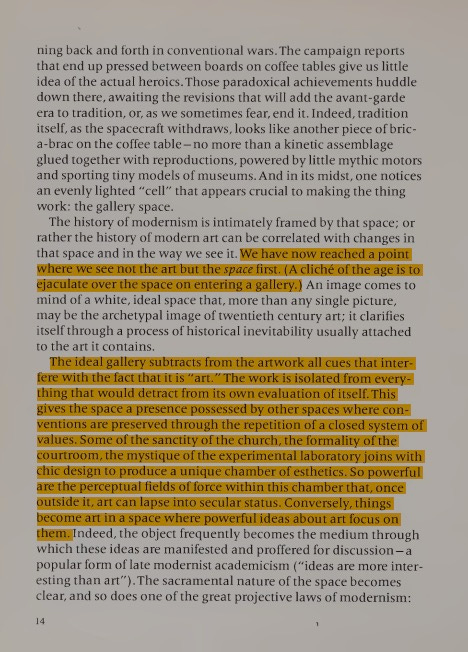

In Brian O’Doherty’s seminal 1976 essay series Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, the author explores the phenomenon of the gallery imposing its identity on the art within it. His particular focus is on the neutral, sterile format of the now-eponymous white cube, which had been prevalent for decades by the 1970s. He makes the case for the white cube being far from neutral (as designed to be), instead sanctifying the art beyond its earthy status and alienating it from the public.

At a time when city blocks are mostly seen as commercial units, I find much romance and integrity in the existence of these galleries. These are spaces entirely devoted to art, whose owners run highly impractical operations (a handful of shows a year, regular renos and repainting of walls) to present art in its best light. The white cube is presented as boundless: it can be modified any which way to accommodate the art; it is a void without intrinsic value, where the art can be perceived “objectively”.

Of course, these spaces are not voids. They are closely intertwined with the gallery brand, how sexy the person is at the front desk (very, always), the director hunched over a MacBook in a walled-off room somewhere behind the art, the follower count, the regular collectors, etc. The polished format of the white cube symbolizes a sort of finality, free from the messiness of the artist’s studio, the failures and breakthroughs, the moments of excruciating doubt, which willed the artwork to life. The space is awarded the power to not only dictate what artwork is “complete”, but what art objects are constituted as “art”. This power of decree is both compelling — the subject of much artistic exploration — and troubling: its seeming infallibility can sour the gallery experience, and perceptions of contemporary art more broadly, for many skeptics.

Artists lament the loss of a tradition, in the Dutch Golden Age for example, when rich people would fund artists’ practices throughout their careers. Patronage today is largely framed as a personal investment with only the side-benefit of supporting an artist, less so as a contribution to the public good. I don’t want to romanticize any period (pick any, it was full of greedy bastards), but commissioning a likeness with your spouse feels positively elegant when today’s billionaires are making Nazi salutes and releasing AI music on their platforms to avoid paying artists.

We’d love to see more art patronage, but it’s unlikely that we’ll nurture a wealthy class inclined towards art for the public good when most of the “good” art is hidden away in rooms the public has not heard of, or is too scared to enter. It’s logical that much of the art would move from these walled-off spaces to private estates, or tax-sheltered storage facilities, rather than public spaces.

We should also consider the impact of the white cube upon artists, which inevitably filters down to the art. Most artists’ vision of success cannot help but include their work situated in the legitimizing light of a white cube. It’s impossible that this destination does not impact the process of creation; it enforces a structure on the art before an idea is formed, which may not have existed were the art simply being made for the sake of expression.

The point above is tiresome in present context. It feels petty to criticize the white cube from this angle when so many artists today are constraining their work to what will best suit a 9:16 vertical video or a 4:5 grid (lord forgive me for knowing these by heart). Relative to those constraints, the white cube feels limitless. I am reminded of an exhibition currently showing at Mercer Union (a white cube) titled The Pleasure Report by the New Mineral Collective: a multimedia installation including audio, lighting, and sculpture, which re-envisions corporate mining reporting under frivolous, romantic parameters. This was designed as an experience; my iPhone documentation efforts were futile.

So what am I getting at? The white cube, and the exhibition space more broadly, is sacred. But not enough prestige, or artistic experimentation, is given to formats which situate art in the public eye and/or allow art to flourish outside of the white cube confines. There is a sense that, outside of the white cube, we have departed the realm of noteworthy “high art”. This feels especially troubling given the current assault on contemporary art spearheaded by parts of the right, which taps into a (valid) populist grievance towards pretentious and inaccessible art spaces.

Call me naïve, but it’s worth considering how differently we would perceive contemporary art if the dominant prestige format was awarded to something other than the white cube e.g. a rotating, community-elected piece in a central neighbourhood location.

To the art world’s credit, the ideas above are widely accepted, even if insufficiently acted upon. Gallerists will be the first to acknowledge the importance of public art projects, not only as a cultural good, but for the development of an artist’s profile. And many contemporary galleries have abandoned the white cube in favour of a less constrained “exhibition / project space” which lacks a template. There are also plenty of artists and collectives detached from a space, moving between white cubes, abandoned buildings, and online formats, as needed for a given project.

On to the ART

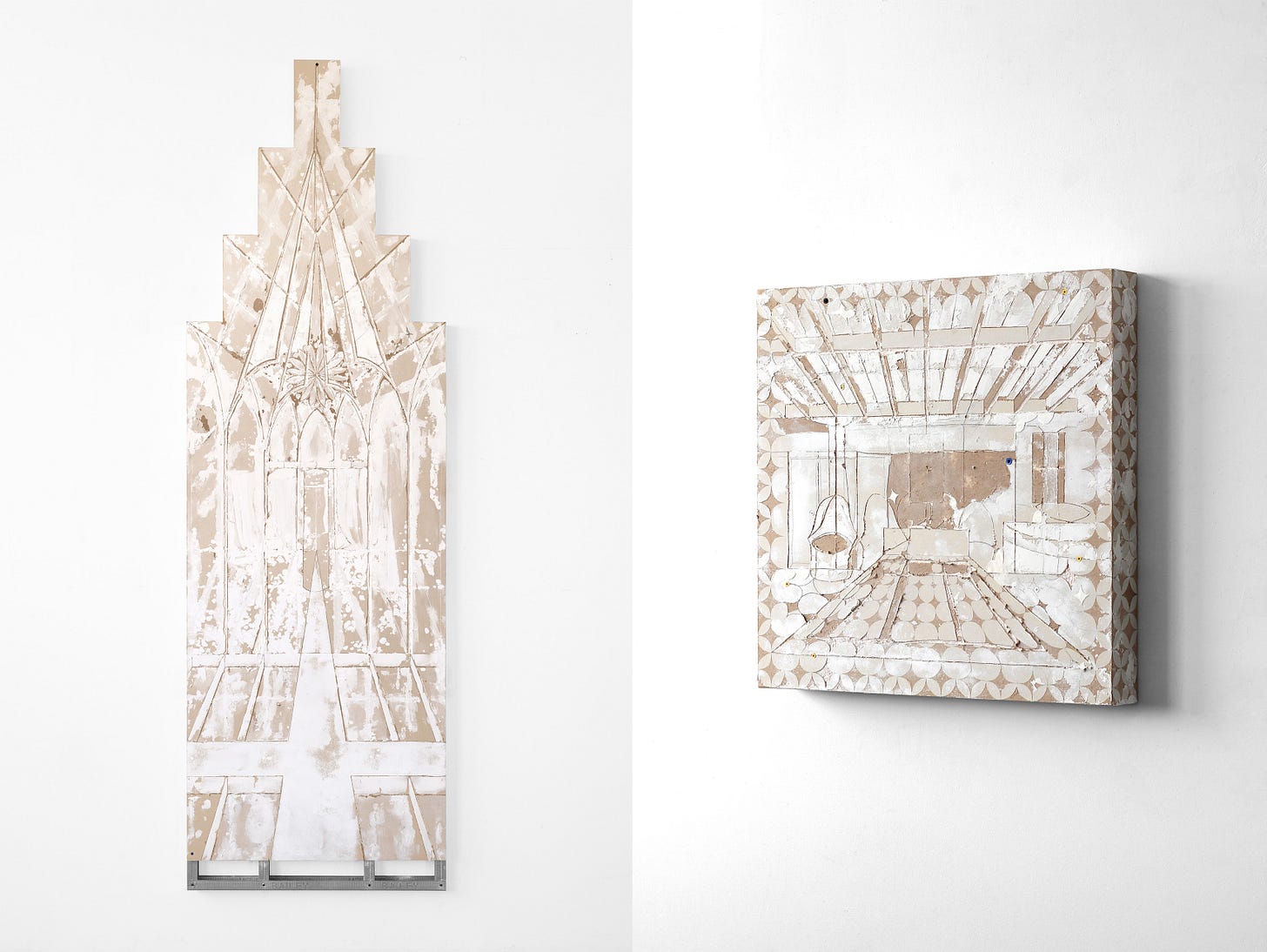

I discovered Simon Petepiece’s work in the white cube of Galerie Nicolas Robert during his exhibition Cleaning Corridor Chamber Cave. His work, fittingly to this essay, explores “how architectural spaces reflect and manifest cultural belief”. In this exhibition, the artist focuses on the cloister’s function of separating monastic order from the outside world, providing an “architectural means of shaping devotional practice”.

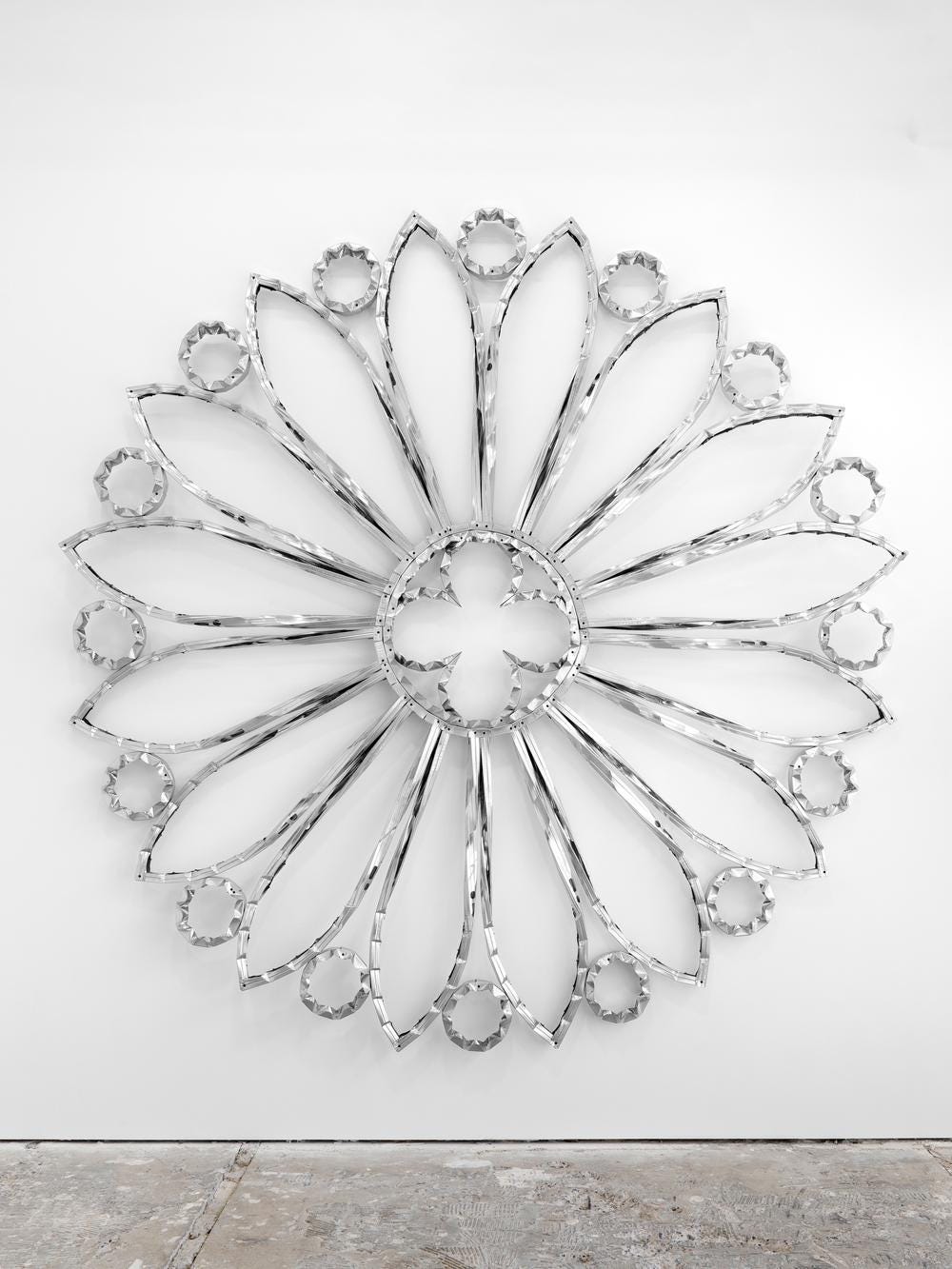

The drywall / joint compound pieces (above) showcasing the interiors of cloister spaces feel like artefacts dug from the ground. They embody the austere quality I would expect from a cloister. The steel installations (below), meanwhile, are an imposing, ornamental presence which feel grating in their scale and jagged finish. I am reminded, strangely, of Reverend Tuttle’s creepy campus in True Detective S01. Placing these objects together, both of which directly symbolize the cloister environment, illustrates how the artist’s (or architect’s) manipulation can impose itself considerably, even totally, on the perception of a culture or a society — both from the inside and out.

This exploration neatly parallels the dynamic of the white cube’s imposition on the art it carries and on perceptions of the art world more broadly.

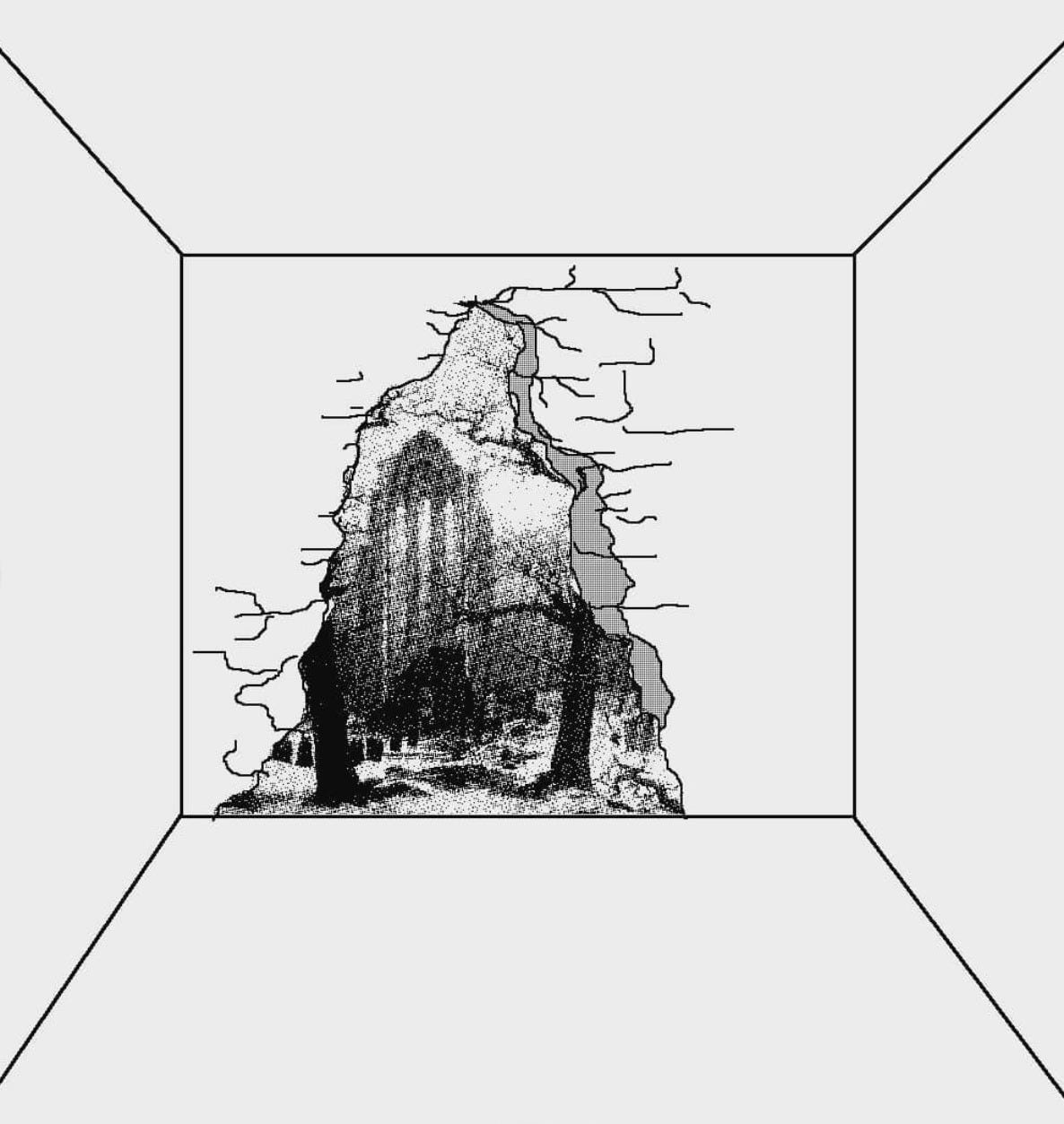

Some months after discovering Petepiece’s work, I came across photographs of his steel pieces, alongside the works of several other artists, presented in a breathtaking outdoor setting by a mysterious curatorial collective (?) titled Eolith. The images were captured at The Sculpted Rocks of Cantley, a defunct sand quarry in Cantley, Quebec. The architect of this geological marvel was the grinding and churning of debris trapped under the Laurentide Ice Sheet ~12,000 years ago, during the last Glacial Period, which resulted in visible striations and gouges in the marble.

I am inspired by the documentation for this project. My research on Eolith revealed little, with an Instagram following of less than 1,000 and their evasive About statement, which is a dictionary definition of the word Eolith:

“A roughly chipped flint found in Tertiary strata, originally thought to be an early artifact but probably of natural origin.”.

These are the esoteric discoveries I live for. It felt like a nice bowtie to today’s essay. Here is an under-appreciated instance of high art, artfully released from the white cube — if only for a moment — and placed on equal footing as rocks, trees, and ruin.

These installations make the art feel more like a human artefact than when placed in the white cube — no matter how sexy those earlier install shots are. At some point, the “important” art will be tucked away into the storage room of a collector, perhaps even an institution. In the meantime, I wish for it to spend as much time in the real world as possible.